by Izeth Hussain (as Published in the Island newspapers of 29th April and 20th May, 2017)

I am on the verge of becoming a nonagenarian, and although my body increasingly refuses to obey my orders my mind is intact and my memory is on the whole reliable. So I can write my autobiography with a fair degree of veracity. I have witnessed changes of a revolutionary order in Sri Lanka over a very long period, and I have witnessed them not just as another Sri Lanka but also from the rather special perspective of a Muslim Sri Lankan. In 1953 I was the first Sri Lankan Muslim to enter the Foreign Service and served in it for 35 years. After retirement I spent five busy and richly rewarding years as a writer, speaker, and participant in many seminars and public meetings. I enjoyed myself punishing the post-1977 UNP Governments for their many misdeeds, and was rewarded by being sent as Ambassador to Moscow in 1995 for three more glorious years of diplomatic life. After 1998 I have been mainly a writer.

I am on the verge of becoming a nonagenarian, and although my body increasingly refuses to obey my orders my mind is intact and my memory is on the whole reliable. So I can write my autobiography with a fair degree of veracity. I have witnessed changes of a revolutionary order in Sri Lanka over a very long period, and I have witnessed them not just as another Sri Lanka but also from the rather special perspective of a Muslim Sri Lankan. In 1953 I was the first Sri Lankan Muslim to enter the Foreign Service and served in it for 35 years. After retirement I spent five busy and richly rewarding years as a writer, speaker, and participant in many seminars and public meetings. I enjoyed myself punishing the post-1977 UNP Governments for their many misdeeds, and was rewarded by being sent as Ambassador to Moscow in 1995 for three more glorious years of diplomatic life. After 1998 I have been mainly a writer.

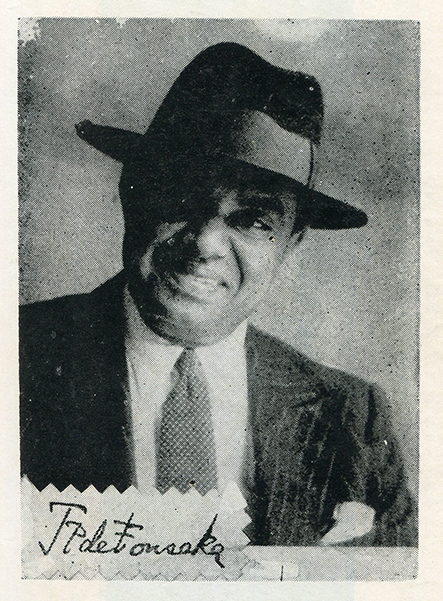

I have found that when I tell my friends that I am thinking of writing my autobiography, they are invariably enthused by the idea. This is not the autobiography I have in mind but sketches for one, which will not be in chronological order. This sketch is inspired by my reading an article recently on J.P. de Fonseka who was a legendary guru at St. Joseph’s, where I was a student until I passed into the University of Ceylon (Colombo) in 1946. He exemplified English literature for us as he had been for many years the secretary of G.K. Chesterton, one of the major figures in English literature of the first half of the last century. He mixed widely with the English literati of that time and was full of anecdotes about them. He surprised us one day by telling us that although his name was always bracketed with that of Chesterton he was never his friend, only his secretary. His close friend in England was Walter de la Mare. I asked him what he was like. JP replied “You have read his poems. He was just like his poems”. He recounted that he used to spend weekends with de la Mare in his country cottage which was situated on the edge of a forest. He had exceptionally sharp hearing and seated on the lawn at twilight could identify every bird by its call. De la Mare is assured of classic status. It occurs to me that JP is perhaps the only Lankan who was a friend of an English writer who has acquired the status of a classic.

Perhaps the most prestigious award at St. Joseph’s was the G.K. Chesterton Essay Prize, for which any student could compete irrespective of seniority. It was usually won by a senior student in the class preparing for entry into the University. Godfrey Gunatilleke who later got a First Class Honours degree in English under Professor Ludowyck, passed into the Civil Service, and founded the Marga Institute, established a record by winning the GKC Prize while in a class just below the entrance level. The next year, in 1943, I established a further record by winning the Prize while in a class that was two years below that of the entrance level. This sounds like boasting and is embarrassing but I see no way of avoiding stating such facts in autobiographical writing. Besides, this particular fact is important for showing that there was absolutely no discrimination on religious or ethnic grounds at St. Joseph’s, long established as the leading Catholic school. Nothing more remote from our ethnic idiocies of the present can be imagined than JP making me float on air by pointing at me and proclaiming “Hussain will be among the contemporary writers in the future”. Not true, alas. A bit of deflation is due after the boasting.

As a teacher of English literature JP was of the old school, placing the focus on appreciation rather than demolition. That was appropriate for teaching the subject at a certain level when the student had to be made to understand and respond to the appeal of good literature. We learnt a lot going through the whole of John Still’s classic Jungle Tide with him, his obiter dicta showing the deep love that he had for this country. Also memorable was the experience of going through Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, which brought alive the text in all its humour. Later, at the University, I had another experience of the play when Doric de Souza brought to bear on it his superb analytical skills. But when I saw the play in London in 1954, to the accompaniment of merry peals of laughter from school girls, it was JP who was brought to my mind.

What is going through my mind is that mine was an extraordinarily lucky generation as far as English and English literature was concerned. Professor Ludowyck was much influenced by his Professor at Cambridge, I.A. Richards, and even more by F.R. Leavis and he insisted on new methods of teaching English literature. The result was that my teacher at the University entrance stage was Augustine Tambimuttu, the younger brother and the favorite younger brother of the famous editor of Poetry London. He used to read out extracts from the air letters he received from London. When the Editor first met T.S. Eliot in a London restaurant, he walked up to him exclaiming “I am going to build a skyscraper of poetry in London”. He was a flamboyant and lovable man – as we found him to be when he visited Colombo – but he had no great ability as poet or prose writer. However, Eliot did esteem him as an editor who could spot talent.

I must write a little more about J.P. de Fonseka who was one of the legendary Josephians of that era. It is not accidental that since his death in 1947 many articles have appeared about him right down the decades, including in recent weeks. As a teacher he made English literature alive for us, and as a writer he wrote a prose that was beautifully lucid. He knew how to put the right word in the right place. He was a frequent contributor to Social Justice, the magazine founded by Fr. Peter Pillai as an antidote to the Marxism that was so formidable in the politics of the ‘thirties and the ‘forties.

But it is to JP as a human being that I want to pay a special tribute. There was an old world charm and graciousness about him, shown in his preference for getting about in a rickshaw when he could well afford a car and chauffer. A recent article gave the impression that he was a rather formidable character. My image of him, and that of my schoolmates, was of a gentle giant who was oozing decency and kindliness from every pore. A devout Catholic, he seemed to us a secular saint. Such people, I believe, exercise a beneficent influence on the life around them, which was the point of one of the most anthologized poems of his friend Walter de la Mare: Here lies a most beautiful lady / Light of step and heart was she. It was not just the physical beauty of a dead female that was celebrated in that poem, but the life in her that made the world around her glow. That was the point also of Ha’nacker Mill, one of the best poems of another of JP’s circle in London, Hilaire Belloc, who was so close an associate of Chesterton that they were known as Chester-Belloc.

It occurs to me that the image of JP that I conceived as a boy was one thing, but from a post-1956 perspective it could be quite another. Was he not a brown sahib, a servitor of British imperialism? The charge has to be met. One of his anecdotes was about his witnessing the classy century scored by Duleep Singh on his test debut at Lords. It was so classy that a crowd gathered outside the pavilion and clamored for him to appear on the balcony, and when he did they cheered him some more. JP claimed that that showed that there was no colour bar in England – “colour bar” was the term we used for racism in those days. He was unmindful of the fact that in the colonial Ceylon in which he was living the British would not mix with the natives, confining their social lives to their exclusive clubs. It seems plausible to argue that that attests to a colonial brown sahib mindset. But we must remember that there was no independence struggle in Sri Lanka worth speaking about: a few Trotskyites were jailed for brief periods and were compelled to read Wodehouse novels, and that was about all. While Nehru was in jail, SWRD was serving in the Cabinet set up by the colonial masters. But the point I really want to make is this: people should be judged not in terms of transient categories and shifting values but in terms of intrinsic worth. As Burns put it – A man’s a man for a’ that. In terms of intrinsic worth, old JP was of grand quality.

The other legendary figure of my time at St. Joseph’s was Fr. Peter Pillai who became Rector after Fr. Le Goc. The little I remember about the latter seems worth putting down. St. Joseph was begun by French priests, of whom the last was Fr. Le Goc. He was thoroughly unconventional as a school Principal because he delighted in joining the boys at playing marbles during the lunch intervals. He was famous for his original work as a botanist, but that did not register on our consciousness at all because what made him a great man for us was his prowess at marbles: he never missed. He was full of stories about his boyhood days in his native Brittany. There seems to have been a tradition of French Catholic priests serving in Sri Lanka for long years. I recall one of them, in the early ‘sixties in Paris, exclaiming on seeing a photograph of Sri Lankan children “Ah the little flowers of Ceylon”. I am recounting such details to make the point that I grew up in a Sri Lanka in which frontiers were easily crossed. We did not feel, as do many Sri Lankans today, that we were being walled up alive. Perhaps the emblematic figure for contemporary Sri Lanka should be Kasyappa.

There was a feeling that under Fr. Le Goc St. Joseph’s was all love and no law and what the college needed to bring out the best in its students was a stern disciplinarian as Rector. That figure was found, supposedly, in the formidable figure of Fr. Peter Pillai. He was a polymath who could have got Firsts and Doctorates in any subject under the sun. But that side of him came out only when he taught maths – he was a brilliant mathematician. He would draw a mathematical problem on the blackboard and announce after a couple of minutes “There are five ways of solving this problem. The first is obvious”. He became famous for his frequent use of the term “obvious”, over matters which were beyond the comprehension of his students. But there was another side to him, shown in his love of tongue twisters which would leave him in merry fits of laughter. He never seemed to me a formidable personage. Indeed, there was something child-like in him. Is that a characteristic of the true holy man, which he certainly was.

izethhussain@gmail.com

http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=164278