If it would occur to any one that the social philosophy which goes today by the name of Distributism is a recent invention like the different topical diseases of the hour which terminate with the suffix, ism, then it is good for his soul to know that a typical poem firmly grounded on the principles of Distributism was written in the Eighteenth Century.

It saw the light of day in a thin quarto on May the 26th-1770 and bore on the title page the words: The Deserted Village, a Poem, By Dr. Goldsmith, Even if Goldsmith hail lived to write the poem in 1870 he would still have been unaware of Distributism but he would have found more and more villages deserted with not another poet left to ask the reason why.

In the dedicatory note to Sir Joshua Reynolds the poet is saying: “I know you will object that the depopulation it deplores is nowhere to be seen, and the disorders it laments are only to be found in the poet’s imagination. To this I can scarce make any other answer than that I sincerely believe what I have written; that I have taken all possible pains to be certain of what I allege: and (that all my views and enquiries had led me to believe those miseries real, which I here attempt to display.” Truth is not only stranger but also more staggering than fiction.

The Deserted Village of the poet is Auburn and numbers of literary critics have speculated on where Auburn could have been and what real name it enjoyed in the world. Auburn was certainly a false name just as certainly as the village was a real village. And much more important than the question of where it could have been situated is the question of what happened to it.

Wherever it was, it’s central and critical fact in history, in its own history as well as in the history, of mankind, is that it was deserted. It had been populated once; and now it was deserted. It was a terrible and even appalling change. But at the time there was not more than one man to notice it or to think it worth notice. This one man was the poet; it moved him to write a, poem; the poem was the<, village’s epitaph, because the village had lived happy for donkey’s years but was now miserably dead. He could not call it back to life, because the poet was a most poverty-stricken poet.

If he had been a poet and a millionaire, subject to a certain limitation, he might have done it. But for poor Nolly Goldsmith it was out of the question. He was a poet continually in debt to his landlady for rent.

In the little balance of dedication left, the poet is saying; “In regretting the depopulation of the country. I inveigh against the increase of our luxuries; and here also I expect the shout of modern politicians against me. For some twenty to thirty years past it has been the fashion to consider luxury as one of the greatest national advantages…..Still I must continue to think those luxuries prejudicial to states, by which so many vices are introduced and so many kingdoms have been undone.”

From this part of the recital it would be clear that the dirty work of depopulating the village was done by luxury. Luxury which the poet fears is able to undo kingdoms undid this village.

This word (and concept), Luxury, dates Goldsmith’s poem. It is a further proof that he had not heard of Distributism. Luxury was his way of saying Capitalism or the money Power. This did it.

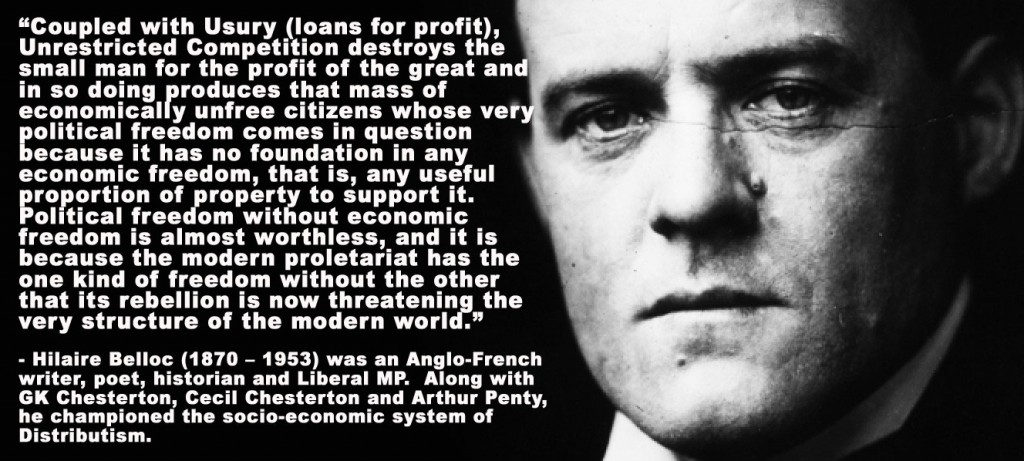

It was the age of the rise of Industrialism, the introduction of machinery and the operation of the legalised highway robbery called the Enclosures. Conversely it was the age of the rise of a proletariat, the beginnings of wage-slavery and the dispossession of the poor. Mr. Belloc has shown that in the fifty years before the accession of George III, 300,000 acres had been enclosed, in the next life-time seven million-one third of the useful land was taken from the “people and went to swell the new capitalist system.”

It was the age of the rise of Industrialism, the introduction of machinery and the operation of the legalised highway robbery called the Enclosures. Conversely it was the age of the rise of a proletariat, the beginnings of wage-slavery and the dispossession of the poor. Mr. Belloc has shown that in the fifty years before the accession of George III, 300,000 acres had been enclosed, in the next life-time seven million-one third of the useful land was taken from the “people and went to swell the new capitalist system.”

The reflection of these notable happenings as seen in Lissoy (or Auburn) was its complete disappearance at one go as a village and its immediate turning up as part of the domain of a wealthy country squire. Sweet Auburn, as one instance of the operation of this process turned up in the squire’s back yard. The millionaire got the village for a song.

In batches of verse which generations of English youth have memorized as a school exercise the poet describes the beauty and felicity of the villager’s corporate life*; its beauty spots, its people, its public characters, its daily routine, its work and play, its self-contained life and sturdy independence. But all this died on the spot, never more to live again, when the new rich ornament of what was to become the English Squirearchy stepped in and annexed Sweet Auburn, loveliest village of the plain.

In equally memorable lines to those which record its felicity the poet then records its high tragedy. Even though he had mentioned the menace of an abstract luxury, the poet still knew the two-legged monster who had swallowed up sweet Auburn whole. For he wrote One only master grasps the whole domain And the dispossessed leave, trembling, shrinking from the spoiler’s hand.

Everyone knows the poet’s celebrated lines:—

Ill fares the land, to hastening ills a prey

Where wealth accumulate, and men decay:

Princes or lords, may flourish or may fade;

A breath can make them as a breath has made:

But a bold peasantry, their country’s pride

When once destroyed, can never be supplied.

The words have become more desperately true of these times than even the poet’s own, for the process which began in his time has achieved its fulfilment only in these days. The poet’s witness to the fact that before the ogre came and absorbed the villages, that is in his words are England’s griefs began there was the traditional votary of small-ownership still part and parcel of the pattern of living and every rood of ground maintained its man. But it is now done with.

But times are altered; trade’s unfeeling train

Usurp the land and dispossess the swain.

And then there take place the division of the robber baron’s spoil and the enclosure of the common land :

Those fenceless fields the sons of wealth divide,

And even the bare-worn common is denied.

And what can the dispossessed do? What do they do? They could accept beggary or flock to the city to accept industrial wage-slavery. But the expropriated of sweet Auburn do neither.

They are migrating, with nothing to carry, to the chances that wait them in the New World across the seas.

They are all going, broken in mind and backbone because uprooted from their proper patch of soil which alone gave them balance and» freedom to call their soul their own.

Social Justice – 1944