The meteoric rise of the Karava during the great economic expansion of the plantation era.

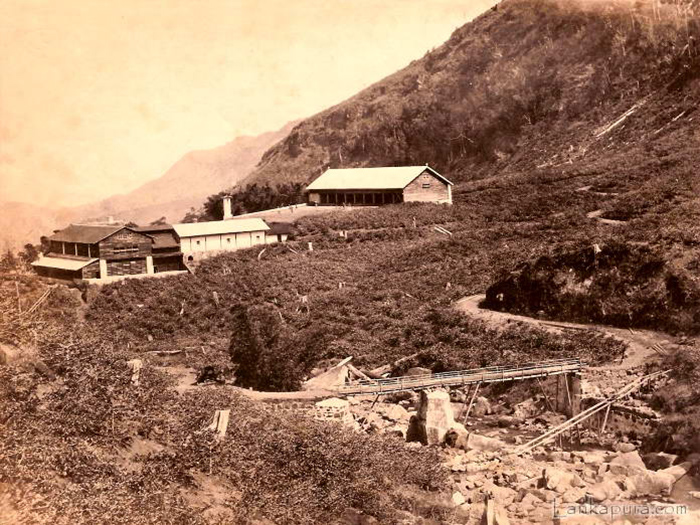

The British continued the Dutch practice of promoting a non-industrial type of capitalism in the form of the plantation system. A few Europeans ran the estates in similar style, organising the daily production of the export crop and utilising institutionalized force to control what was virtually a domain. Plantations were opened up with foreign capital on cheap crown land, which were managed by British superintendents, producing an export crop almost exclusively for sale and consumption in foreign markets. The work force was composed of immigrant South Indian labor.

The growth of the plantations also required the development of a network of roads, the railways and the port. A vigorous policy of road building was undertaken and the Colombo Kandy railway was completed in the year 1867. A string of feeder roads to feed the railway, and roads to the interior of the country were also built during these years. These large-scale building activities also bought a large workforce to these areas. This also gave a good economic opportunity to the local cart contractors, labor contractors, construction workers and mills to provide services. Another important event was the abolition of Rajakariya (a system of compulsory unpaid labor to the state) in the year 1833, which resulted in a large base of paid labor. This combination of the opening of the interior, the large immigrant plantation work force, the large road building workforce and railway workforces and the other construction, cart transport and feeder services labor and the military, all with an expendable income, gave rise to a meteoric growth in the consumption of liquor. The renters who were prospering due to this, vertically integrated with the supply chain, buying and controlling the distilleries. They also formed cartels thru kin and caste relationships to control the bidding and the amounts of rents paid to the government, a crude form of monopolistic control and oligopoly as practiced in today’s’ economy.

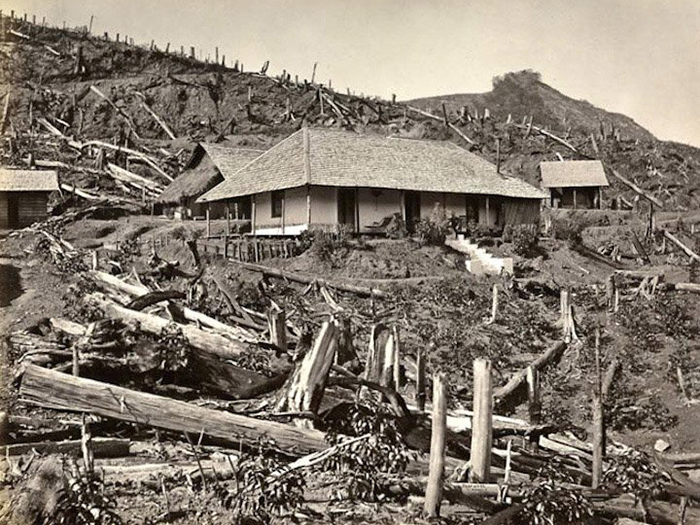

The fortunes made from renting gave them enough money to venture out into other available avenues of investments, mainly plantations, mining, acquisition of land and urban property and the practice of the professions. Such investments in the economy and education formed the elite class in later years. The acquisition of land gave status and prestige to the renters, as in earlier periods the kings created nobility through the granting of lands. Most successful renters took to plantations and land acquisition so much that the second generations concentrated only on these new investments. In fact biographies of some of these families make either no reference (or only a passing allusion) to the profits reaped from the arrack businesses. The initial foray into the plantations was mainly in the coffee, with the karava soysas owning over 3000 acres of planted coffee in the early periods. With the fall of the coffee plantations in the 1880s, coconut and rubber also became an important economic base. Tea was mainly a British preserve, with some Sri Lankans planting in the low and mid country regions. Rubber was a more important investment to the locals. Introduced in 1875, the growing areas expanded mainly in the Kalutara, Galle and Kelani Valley districts. E.C De Fonseka, Fred Abeysundera and Alice Kotelawela are among the non-liquor bourgeoisie large rubber owners owning over 1000 acres (1927), listed by Roberts (1979:180).

One other investment that was almost the exclusive preserve of Sinhala capitalists was the mining of graphite (plumbago), and had close connection with the arrack renting. Several leading Karava renters owned graphite mines.

To those without personal fortunes, education proved to be the main vehicle of achievement. In a society that respected the learned persons, most families of petty bourgeois pooled all resources to educate the best among them. Sinhala and Tamil men increasingly entered the medical and legal professions. Many of these professionals married into rich families, with doctors and lawyers being in demand. As colonial institutions were democratised, greater opportunities arose for these professionals.

The Karava Capitalists:

The association between occupation and caste ceased to be observed in the late colonial periods, due to the new non-caste occupations that cut across all caste lines. In 19th century Sri Lanka, the goyigama was the prestigious and the largest caste group, and also formed the majority of the Sinhala population. (The goyigama of the land owning mudaliar groups, who were designated ‘first class’, distinguished themselves from the average goyigama, and later on used the term Radala to describe themselves.) However this was to change in the turn of the century with many karava families accumulating wealth and prestige. Roberts (1982:115) who did a caste analysis from A. Wright’s book ‘Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon’ revealed that, of the 248 names where the caste could be identified, 51.2% was goyigama (against a population over 50%) and 43% from the karava, durava and salagama castes, where all three castes formed only 31% of the population. Roberts points out that the karava alone having 35.8%, has done relatively well for themselves.

Attention has also been drawn to the caste controversy between the goyigama and the karava castes. Although formally expressed in terms of caste, its contents can be better construed as arising from the two sections of the bourgeoisie class, the land owning goyigama group and the new merchant capitalist (heavily karava).

Of the new karava capitalists, the following were some of the leading families of the period. Warusahennedige Soysa the richest and the most powerful of the Singhalese capitalists, Hennedige Jeronis Pieris, protégé and cousin of Soysa, Vidanalage de Mels of Moratuwa, renters and leading graphite merchants, Telge Peiris family of Panadura, Lindamulage de Silvas of Moratuwa, Hanwedige Peiris of Moratuwa, Ponnehennedige Dias family of Panadura including Jeremias Dias, Merennege Salgado family of ‘Salgado Bakery’ fame, Hettiakandage Fernando of Kalutara and the de Silva Amerasuriya family of Galle.

The Karava in Politics:

One of the key battles of the new rich was the issue of representation in the Legislative Council that has existed virtually unreformed from 1833 to 1912. The council of 15 members was composed of nine senior government officials and a minority of six ‘Un-officials’, appointed from among the ‘higher classes of natives’ from various ethnic groups. The person nominated to represent the Sinhalese was always drawn from the first-class goyigama mudqliar clans. The Karava made many representations to elect their highly qualified members to the legislature. In 1882 a class organisation of capitalists formed by the name of Ceylon Agricutural Association. This consisted of the most prominent karava capitalists of these years including S. R. de Fonseka. In 1888 the name was changed to ‘Ceylon National Association’, a bold step towards making it a more political organisation. The change had been initiated by Walter Pereira, Telge Charles Peiris and S. R. de Fonseka, but led to Charles de Soysas disapproval and resignation. In 1888 this group again attempted to gain entry to the Legislative Council, but failed.

The continuous campaign of the new group of capitalists only succeeded in 1912, when A. J. R Soysa, second son of Charles de Soysa was nominated as the second low country Singhalese member. The electoral reforms of 1920s which launched a limited franchise and the subsequent reforms of 1931 which launched universal franchise, brought about significant changes. The legislatures of the 1920s, elected from a restricted base of 4% of the population and including nominated members, proved to be the heydays of the karavas. But with the extension of territorial representation in 1925, the proportion declined, and with universal franchise in the 1930s, there was a further sharp reduction.

The new faces in the 1931 State Council included Susantha de Fonseka (Panadura), son-in-law of Mathes Salgado (arrack renter and founder of a chain of bakeries); John L Kotelawala (Kurunegala), Henry W. Amerasuriya(Udugama) and S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike. Of the 50 elected 76% were Singhalese, of which the karava members Dr. A. E Cooray, Henry Amerasuriya, Dr. W. A. De Silva and Susantha de Fonseka constituted 10.5%. In the 1936 elections this wend down with the defeat of Dr Cooray. The new board of ministers included one karava minister Dr W. A. de Silva. From 1942 to 1947 there were no karava ministers, but in 1948 this changed with the inclusion of Henry Amarasuriya.

Author’s Note: The excellent book by Kumari Jayawardena cited in the Bibliography, is the base for this article. This book explores the rise of a bourgeoisie class who acquired wealth during a time of capitalist development in the 19th and 20th century colonial periods. The De Fonseka families however failed to make use of the emerging economic opportunities. Most of the Mudaliyar class made use of their position to good use, investing in rentals, crown lands and other opportunities. The aristocratic De Fonsekas/D’andrados initially looked down on the ‘New Rich’, but were to marry into these families in later years .

Bibliography:

‘Nobodies to Somebodies – The Rise of the Colonial Bourgeoisie in Sri Lanka’ by Kumari Jayawardena.