This well researched article, written in 1921 by Lionel de Fonseka, is referred to by almost all subsequent ‘Karava’ historians. The article appeared in the Ceylon Antiquarian and Literary.

The Karave Flag (see note at bottom) is a document well worthy of antiquarian attention, Its provenance has already been indicated by Mr. E. W. Perera in his monograph on Sinhalese Banners and Standards.

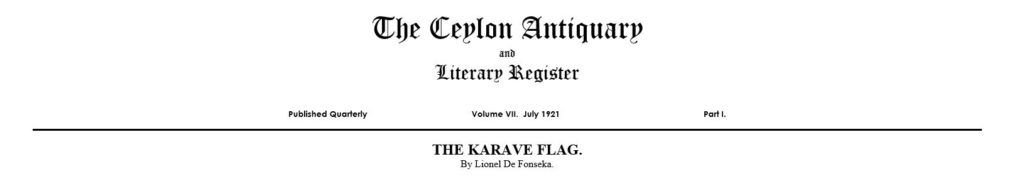

The flag holds within its borders a unique collection of antique emblems, many of which were highly expressive not only to the Sinhalese but to all the civilized peoples of the ancient world. Some of these symbols are now obsolete, while a few have remained current to our day. The following is an essay to trace the import of each of the symbols on the Karave flag, and to render their collective significance as the emblems of the Kaurava Vanse.

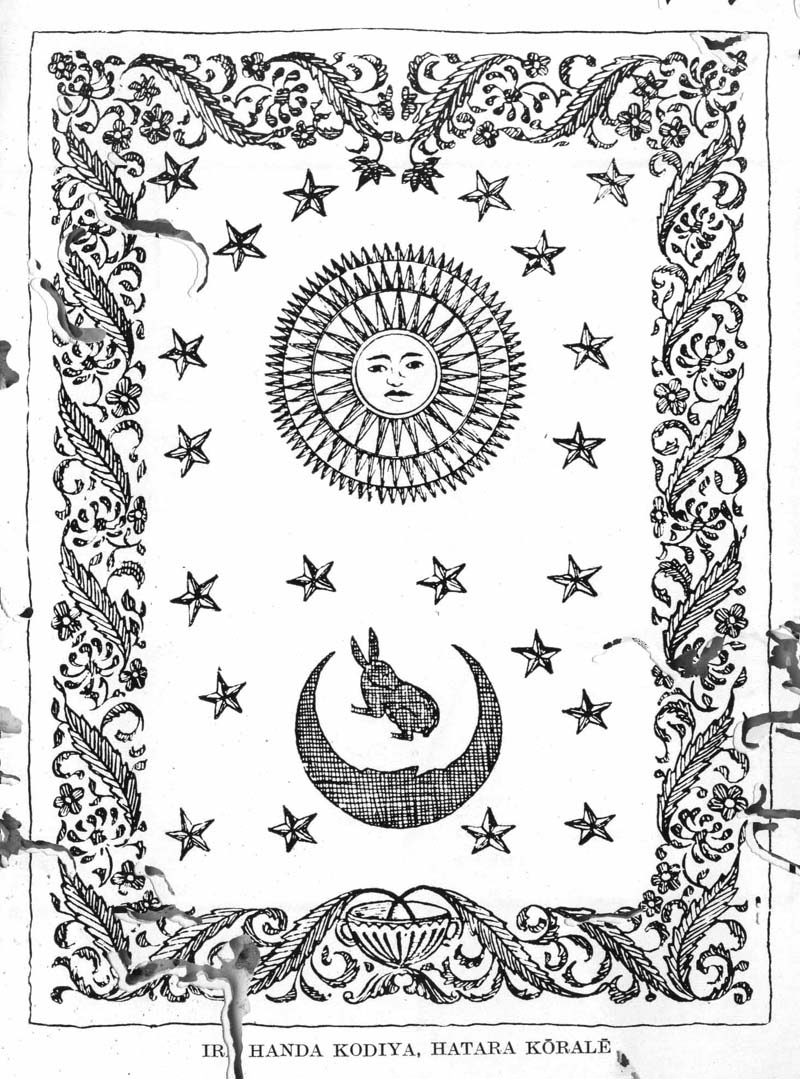

(1) The Sun, Moon and Stars.

The Rajput clans of India adopted the emblems of the sun and the moon, according to their descent from the Solar or Lunar race. The sun and moon were in a special manner the emblems of the Royal house in Ceylon indicating its Kshatriya descent from the Solar and Lunar races. The Ivory Throne in the Brazen Palace at Anuradhapura was adorned with the sun in gold, the moon in silver, and the stars in pearls. The façade of the Old Palace at Kandy was adorned with the same emblems in plaster relief. The sun and moon as emblems in the Royal house of Ceylon figure almost invariably on royalinscriptions and grants. These emblems were not depicted on grants, as is sometimes supposed, as “symbols of perpetuity” – the phrase so common in grants ” as long as the sun and moon endure,” being derived from the royal emblems, not the emblems from the phrase.

The Rajput clans of India adopted the emblems of the sun and the moon, according to their descent from the Solar or Lunar race. The sun and moon were in a special manner the emblems of the Royal house in Ceylon indicating its Kshatriya descent from the Solar and Lunar races. The Ivory Throne in the Brazen Palace at Anuradhapura was adorned with the sun in gold, the moon in silver, and the stars in pearls. The façade of the Old Palace at Kandy was adorned with the same emblems in plaster relief. The sun and moon as emblems in the Royal house of Ceylon figure almost invariably on royalinscriptions and grants. These emblems were not depicted on grants, as is sometimes supposed, as “symbols of perpetuity” – the phrase so common in grants ” as long as the sun and moon endure,” being derived from the royal emblems, not the emblems from the phrase.

The sun-and-moon flag (ira-handa kodiya) has long been specially associated with the Kaurava Vanse. According to one tradition, the Ira-handa kodiya, the Makara kodiya, and the Ravana kodiya were presented by the king to certain Karave chieftains who defeated a body of Mukkuuvars on the coast of Puttalam.

“When Sri Prákrama Bahu Maha Raja,” says an old Sinhalese account, was reigning at Cotta, a hostile people of the name of Mukkara landed in Ceylon and got possession of Puttalam. The King Parákrama Báhu wrote to the three towns Kanchipura, Kaveri-pattanum, and Kilikare, and getting down 7,740 men defeated the Mukkara and snatched the fort of Puttalam from their hands. The names of those who led this army were Vaccha-nattu-dhevarir, Kurukula-nattu-dhevarir, Manikka.Thalaven, Adhi-arasa adappan, Warnesuriya adappan, Kurukulasüriya mudali,” Arsa-Nilaitte Mudali, etc. (See letter by Mudaliyar F. E. Gunaratne, in the “Ceylon Independent,” 11th April, 1921.)

The king on the same occasion granted them certain villages and domains, including Maha-vidiya, and Velle-vidiya in Negombo.

The sun-and-moon flag was also the flag of the Four Kórales. According to tradition, “when the god-king Rama proceeded from Devundara to Alutnuwara in great state, with a four-fold army like unto a festival of the gods, the flag emblazoned with the sun and moon was borne in front. Since then the Four Kórales held chief rank.”

This explanation is intelligent, but hardly goes far enough. According to Dr. Paul Pieris, the people of the Four Kórales “were considered the most noble of all in Ceylon . . . Some of the families, for instance the Kiravelli, were recognized as representing the true royal stock. The martial prowess of the men of the Four Kórales was always recognized, and their maha kodiya, emblazoned with the sun and moon, was allotted the place of honour in the van of the army.” ( Portuguese Era I. 316.)

We are led to suspect from this that the sun and moon emblems in the case of the Four Kórales were primarily associated with the noble birth of the inhabitants, and, if we turn to the Kadaim-pot, this suspicion will be confirmed. There we find that there was a district in Ceylon known as the Kuru-rata, conterminous more or less with the region of the Four Korales, and the inhabitants of the Kuru-rata in Ceylon were believed to have come from the Kuru-rata (Delhi district) in India.

According to the Kadaim-pot (see Bell, Kegalla Report, p 2) “in ancient times. . there came to this island from the Kuru-rata a queen, a royal prince, a rich nobleman and a learned prime minister with their retinue, and by order of King Rama dwelt in that place called on that account Kuru-rata. In the year of our great Lord Gautama Buddha, Gaja Bahu who came from Kuru-rata settled people in that district, calling it Paranakururata . . .”

Paranakuru is one of the divisions of the Four Korales, and, according to Dr. Pieris, Siyane Kórale was also in former times a division of the Four Kórales. It is, to say the least, a remarkable coincidence that the Royal family, the men of the Four Kórales, and the Kaurava Vanse, all of whom, and who alone, authentically used the Ira-handa-kodiya, should be reputed to be of Khattriya descent.

Kuru-rata is the district in India whence the Kaurava Vanse claims its ultimate origin, and, if we turn to the list of Karáve chieftains who rescued the fort of Puttalam, the names of some are sufficiently indicative of their origin. Kuru-Kula-nattu-dhevarir is one chief Vaccha-nattu-dhevarir is another. Now Vaccha was a town in N. India, called also Kausambi the capital of Nemi-.Sakkaram, King of Hastinapura, who transferred his capital to Vaccha. Vaccha-nattu-thevagay is still the name borne by certain Karave families of Siyane Korale, where some of the oldest Karave families are resident.

If we turn to those flags where the sun and moon occur in conjunction with other emblems, in Mr. E. W. Perera’s exhaustive monograph on flags, we find that the Sun and Moon figure on the banners of the kings Dutu-gemunu and Mahasena, on the flags of certain ancient temples of royal faoundation, such as Kataragama, on the flags of certain dissavanis which were at one time ruled by members of the royal family, such as the Seven Kórales (ruled by Prince Vidiye Bandara), and Uva, which in Portuguese times at any rate, was always a royal principality, the only Prince of Uva who was not a member of the reigning house being Antonio Barretto, or Kuruvita-Rala who was apparently of the Kaurava Vanse, De Queiroz describing him as a pescador or fisher.

The sun and moon seem therefore to have been the most jealously guarded emblems in ancient Ceylon, those privileged to use these emblems being privileged apparently on the ground of descent rather than merit.

(2) The Pearl Umbrella.

From time immemorial the umbrella has been among Oriental peoples a symbol of dominion. What is probably the earliest representation of the Umbrella in Ceylon is described by Neville in the Taprobanian (Dec. 1885). He there describes a stone panel discovered by him among the ruins of a very ancient city, (which he ascribes to the primitive era of pile-dwellings),

From time immemorial the umbrella has been among Oriental peoples a symbol of dominion. What is probably the earliest representation of the Umbrella in Ceylon is described by Neville in the Taprobanian (Dec. 1885). He there describes a stone panel discovered by him among the ruins of a very ancient city, (which he ascribes to the primitive era of pile-dwellings),

In the district of Puttalam. The panel in question represents a five-headed Naga seated beneath an umbrella, and two hands on either side holding a chamara.

Indian monarchs often styled themselves, “Brother of the Sun and Moon, and Lord of the Umbrella.”

It is probable that in ancient times the umbrella was primarily thought of as a parasol rather a parapluie. The umbrella figures as an emblem of dominion on Assyrian reliefs and Egyptian wall-paintings. On a relief from Nineveh in the British Museum a conquering monarch sits under the parasol and received the homage of the vanquished. On another the King sits under a parasol and directs a siege. An Etruscan sepulchre, discovered at Chiusi, depicts a lady witnessing the palaestic games, “seated beneath an umbrella, indicative of her rank and dignity.” (Dennis. Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria).

The parasol (skiadion) often figures on Greek vases, generally in the hands of an attendant. It was used as a token of respect, in religious processions at Athens, the daughters of the metoics (or resident aliens) having to hold parasols over the heads of the Kanephoroi, the Athenian maidens who carried the baskets of sacred bread. The use of the parasol has survived to this day in the ceremonial processions of the Catholic Church.

Ovid in the Ars Amatoria, advises the Roman gallant to be attentive with the parasol, and it is possible that Roman clients flattered their patrons with the parasol, on their way to the Forum. Whoever has seen a village litigant in Ceylon, leading a train of clientes, and differentially holding the umbrella over the head of an outstation proctor on his way from office to court-house, will guess that the Sinhalese custom must have had a Roman analogy.

The parasol figures on the paintings at Ajanta (200 B.C.) as an emblem of royalty. It is there represented as decked with streamers and garlands of flowers, from which doubtless were derived the garlands of pearls on the ” pearl umbrella,” as used in Ceylon. The parasol figures also on the carvings of the stupa of Bharut, on the panels of the East gateway at Sanchi, and on the ancient Buddhist carvings of Java.

An Indian inscription of the 12th century speaks of the king’s ” white parasol raised on high, like a matchless second moon, overspreading the whole world”. During the reign of Rájádhirája I Cholan (1018-1053 A.D.) the Pandyans combining with the Sinhalese and the Cherans, tried to throw off the Cholan yoke, but were defeated. The victor’s inscription (S. Ind. Inscriptions, III. 56) states that he ” drove down to the river Mullaiyar Sundara Pandya of great and undying fame, who lost in the stress of battle his royal white parasol, his fly-whisk of white yak’s hair, and his throne.” In 1844, when the Amir Abd-el-Cader was worsted by the French arms in Algeria, the loss of his parasol was the token of his defeat.

The pearl umbrella has been one of the most conspicuous emblems of royalty in Ceylon. “The white umbrella of dominion, studded with jewels and fringed with pearls, was borne aloft on a silver pole surmounting the throne,” (see the Mahavanse, and E. W. Perera Ancient Sinhalese heraldry.) In preparation for the arrival of the Relics, Mahinda tells Devanam-piyatissa, ” Go thou in the evening, mounted on thy state-elephant, bearing the white parasol” (Mahavanse). Just before the enshrining of the Relics, Dutthagamini is seen standing, “holding a golden casket under the white parasol” (Mahavansa).

“The parasol was the emblem most directly associated in the popular mind with duly constituted authority and kingly rank. . . To bring the country ‘under one parasol,’ signified consolidating the government under one sovereignty.” (John M. Senaviratne: Royalty in Ancient Ceylon).

According to Ehelepola, the pearl umbrella was in his time an emblem of royalty. It is still used by members of the Kaurava Vanse on ceremonial occasions.

It is probable that the use of pearls on the royal umbrella became de rigueur in Ceylon, following the Pandyan precedent. The lost city of Korkai, once the capital of the Pandyan kings, was the centre of the pearl fishery, and is spoken of as a noted pearl emporium by Ptolemy. The prestige of the Pandyan kings was based on pearls, as that of the Sinhalese kings was based on gems. The kings of Madura until comparatively recent times styled themselves ” Chiefs of Korkai.”

(3) The Chamara.

![]() The chamara or ceremonial fly-whisk is a royal symbol of great antiquity. A relief of Assur-bani-pal and his queen in the British Museum depicts attendants holding chamara. The ancient panel depicting depicting a five-headed Naga discovered by Neville contains Emblem.

The chamara or ceremonial fly-whisk is a royal symbol of great antiquity. A relief of Assur-bani-pal and his queen in the British Museum depicts attendants holding chamara. The ancient panel depicting depicting a five-headed Naga discovered by Neville contains Emblem.

In India, the royal chamara were made of the white hair of the Tibetan yak, (see the Cholian inscription referred to above); and Barbosa (1514) describes the whisks used by the king of Ceylon as made of the ” white hair of animals.” Vimala Dharma I, offered a gilt-handled whisk as a royal emblem to Pinhao. A specimen of an ivory handled whisk may be seen among the ivory exhibits at the Colombo Museum. At the enshrining of the Relies, Samtusita is said to have held “the yak-tail whisk.” (Mahavansa).

The chamara appears in the hands of the “daughters of the gods” attending on the higher gods, at Sanchi. It appears also on the paintings at Ajanta. Here, in addition to its use as a whisk, three chamaras at the end of a spear, figure as a special symbol, among time paraphernalia of war. This usage appears to have survived in the Turkish army till the 18th century. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, in one of her letters describing the departure of a military expedition from Constantinople, speaks of the “pashas of three tails,” and of these emblems being displayed in front of their tents as “ensigns of their power.”

(4) The Chank.

The chank or conch-shell was in its origin a martial emblem. As a religious symbol it was particularly associated with Vishnu, who is declared to have used it in war. Its use as a trumpet in war is constantly spoken of in the Mahabharata. Chanks as trumpets are depicted in a representation of a royal procession at Buddhagaya on the occasion of Mahinda’s mission with a branch of the bo-tree to Ceylon, carved on the East gateway at Sanchi.

The chank or conch-shell was in its origin a martial emblem. As a religious symbol it was particularly associated with Vishnu, who is declared to have used it in war. Its use as a trumpet in war is constantly spoken of in the Mahabharata. Chanks as trumpets are depicted in a representation of a royal procession at Buddhagaya on the occasion of Mahinda’s mission with a branch of the bo-tree to Ceylon, carved on the East gateway at Sanchi.

Father Barradas, a Jesuit missionary, mentions the use of chanks as trumpets at a Karáve wedding procession at Moratuwa in 1613.

As an emblem of royalty, the chank figured on the royal shield, which was white, and bore this device, and was called the sak paliha (conch shield). “Not long after the king of the hill country raised a rebellion in the Hatara Korale, Dharma Prakrama Bahu (1505-1527) having heard of this, committed the army to his younger brother . . . and sent him to seize the hill country . . . The king of the hill country came to meet him, and in token of homage sent the pearl umbrella, the conch shield and chain of honour” (C.B.R.A.S. Journal xx, p. 187).

The chank was one of the emblems which adorned the canopy over the Ivory Throne at the Brazen Palace. It figures, with the sun and moon and the wheel of empire, on grants made by the Sinhalese Kings. It is mentioned as an emblem of royalty in Vimala Dharma’s letter to Pinhao offering him a kingdom.

“Dom Joao of Candia to Simao Pinhao, King of the kingdoms below…

“Your honour will be king of the territories below, of which Raju was the lord… I for my part make this promise and there is no uncertainty as to my word… For your honour, a collar of Raju two bracelets for each arm, all of precious stones, the honour of anklets for the feet, one pitcher and basin of gold, with a gilt palanquin; two white parasols, two white banners, a white shield, a chank, and chamara, all gilt.” (Pieris, Port, Era I, 357).

(5) and (6) The Sword and Trident.

“The man represented on the flag as seated on an elephant is probably the chief of the tribe. . The elephant has been associated with the caste on tombstones of the seventeenth century.” (E. W. Perera Sinhalese Banners and Standards.)

“The man represented on the flag as seated on an elephant is probably the chief of the tribe. . The elephant has been associated with the caste on tombstones of the seventeenth century.” (E. W. Perera Sinhalese Banners and Standards.)

The chief bears in his right hand a sword, and in his left hand a trident. These again were emblems of royalty.

Barbosa (1514) describing a progress of the Sinhalese King, says, “When the king goes out of his palace, all his gentlemen are summoned who are in waiting. And one Brahman carries a sword and shield, and another a long gold sword in his right hand, and in his left hand a weapon which is like a fleur de lis (i.e. a trident). And on each side go two men with two fans, very long and round, and two others with two fans made of white tails of animals, which are like

Horses.”

The trident appears also on coins and royal inscriptions.

(7) The Torches.

The dawalapandam or daylight torches are still used by the Karáve people on ceramonial occasions. Barradas observes the custom (“candles lighted in the day-time”), at a Karáve wedding procession in 1613.

The dawalapandam or daylight torches are still used by the Karáve people on ceramonial occasions. Barradas observes the custom (“candles lighted in the day-time”), at a Karáve wedding procession in 1613.

Barbosa speaks of the torches as part of the royal insignia, though he appears to have been under the impression that they were used only at night, having probably witnessed a royal progress at night-time: “And if the king goes by night, they carry four large chandeleers of iron, fall of oil with many lighted wicks.”

A specially interesting feature in the torches depicted on the Karáve flag is the fact that these are chandeleers with many lighted wicks, and each chandeleer carries five distinct lights. Neville (Taprobanium, April, 1887) makes some interesting observations on these torches with the five lights, which he saw used at a fire-passing ceremony in honour of Draupadi and the five Pandavas. The use of the caste-flag appears to have been an essential part of the ceremony, and at Chilaw, where the rite was practised in its purest form, Neville observed that the caste-flag was the Makara “representing the Varna-Kula.”

This rite in honour of the five Pandavas was specially practised on the Coromandel Coast between Negapatam and, Kurnool, (Indian Antiquary 1873), presumably by a people who had special traditional reasons for commemorating these heroes of the Mahabharata. Contingents of Karáve soldiers reached Ceylon at different times from the Coromandel Coast, for instance, in the time of Parakrama Báhu VI., from Kanchipura, Kavéri.pattanam, and Kilikare, and there is little doubt that the ritual of the five Pandavãs was introduced into Ceylon by them, the same clan-names, Varnakula, Kurukula, etc., occurring to this day among Karáve people in Ceylon, and on the, Coromandel Coast, at Negapatam and elsewhere. (Thurston, “Races of South India.”)

With the custom of the five-wicked torch commemorating the five Pandavas, it seems pertinent to compare the Karáve custom, which was remarked by the Portuguese Jesuits at

Chilaw in 1606, of having five Pattangatins or chiefs to rule their communities (Ceylon Antiquary Jily, 1916).

The torch (sula) occurs, often in conjunction, with the fish, on a series of royal inscriptions in the Tissamaharáma district.

The use of the ceremonial torches was sometimes conceded by the king (e.g. on the Uggalboda sannas of the 15th century) to privileged individuals as a mark of high distinction.

(8) The Fans. (Alawattam)

The fan as an emblem of honour has a respectable antiquity. It occurs, with the whisk, on the relief of Assur-banipal and his queen referred to above. An Etruscan sarcophagus, now in a museum at Rome, holds a releief depicting a matron, with attendants on either side, one of whom holds a hydria on her head and a cantharus in her hand, another with a large fan, “exactly like the Indian fans of the present day.” (Dennis, Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria).

The fan as an emblem of honour has a respectable antiquity. It occurs, with the whisk, on the relief of Assur-banipal and his queen referred to above. An Etruscan sarcophagus, now in a museum at Rome, holds a releief depicting a matron, with attendants on either side, one of whom holds a hydria on her head and a cantharus in her hand, another with a large fan, “exactly like the Indian fans of the present day.” (Dennis, Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria).

This Etruscan use of the pitcher, beaker, and fan, calls to mind the offer of a pitcher and a beaker of gold as royal emblems by a Sinhalese King, and the use of the pitcher and the fan among the emblems on the canopy over the Ivory Throne at the Brazen Palace.

The Gandhara relief, in the Lahore Museum, represents the Buddha attend by a Vajrapani holding a fan.

Borbosa’s mention of the fans among the insignia of the king of Ceylon in 1514 has already been referred to. Pridham describes their use by the First Adigar at Kandy, the talipots, according to him being “large, triangular fans, ornamented with talc.”

The use of the talipots and the lion flag were conceded by the king to a chief in the Uggalboda sannas, together with the use of the ceremonial torches.

(9) The Shields.

The shields depicted on the Karáve flag are white, and each bears a device in the centre. The “white discs” used at the Karáve wedding at Moratuwa in 1613, were either shields (shields in ancient Ceylon being always circular), or they were affixed to a pole and borne as maces, as represented on the Ajanta paintings. Barrados’ account of the wedding is as follows:-

The shields depicted on the Karáve flag are white, and each bears a device in the centre. The “white discs” used at the Karáve wedding at Moratuwa in 1613, were either shields (shields in ancient Ceylon being always circular), or they were affixed to a pole and borne as maces, as represented on the Ajanta paintings. Barrados’ account of the wedding is as follows:-

“The wedded pair come walking on white cloths, with which the ground is successively carpeted, and are covered above with others of the same kind, which the nearest relatives hold in their extended hands after the fashion of a canopy. The symbols that they carry are white discs, and candles lighted in the day-time, and certain shells which they keep playing on in place of bag-pipes. All these are Royal Symbols which the former kings conceded to this race of people, that being strangers they should inhabit the coasts of Ceilao, and none but they or those to whom they give leave can use them.”

Apparently the wedding described here was one of the poorer class of Karáve people, the white cloth held as a canopy taking the place of the pearl umbrella.

Barrados goes on to observe, “what causes wonder in this and in other people of this kind, is, that although so wretched, miserable, and poor, they have so many points of honour, that they would rather die than go contrary to it.”

The royal shield appears to have resembled the Karave shield: “The royal shield was white, with the device of a conch-shell.” (E. W. Perera. Sinhalese Banners and Standards.)

De Barros speaks of the Crown Prince of Jaffna being conspicuous on a certain occasion by the white shield which he bore. (C.B.R.A.S. Journal Vol. XX.)

A Portuguese general had with him “as a badge of royalty” two Mudaliyars with white shields. (C.B.R.A.S. Journal XI. 574). The use of the white cloths, white canopy, and white shields at the Karave wedding described above by Bàrrados is significant. “White was the royal colour. Its use was limited by sumptuary law to particular privileged individuals and classes.” (E. W. Perera: Ancient Sinhalese Heraldry.)

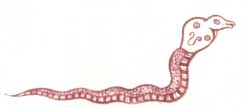

(10) The Snake.

The snake on the Karáve flag has every appearance of being a full-blooded Cobra. Mr. E. W. Perera, (Sinhalese Banners and Standards), describes the snakes as diya-naya or water-snake.

The snake on the Karáve flag has every appearance of being a full-blooded Cobra. Mr. E. W. Perera, (Sinhalese Banners and Standards), describes the snakes as diya-naya or water-snake.

A snake and a fish were included among the twenty-one emblems of an Indian King (Gazatteer of India, Madara District.)

Some authorities omit the snake, and include two river fishes among the emblems of an Indian King: (See the Diet, of European Mission Pondicherry.)

Mr. E. W. Perera has apparently, either from a slight confusion of ideas or a strong sense of economic justice, transferred the river-attribute of one of the fishes to, the snake.

(11) The Fish.

The fish was one of the emblems of royalty in India, Among the Hindus, the fish was regarded as a sacred animal. “One of the principal articles of the Hindu faith is that relating to the ten avatars or incarnations of Vishnu. The first and earliest is called the Matsya-avatar, that is the incarnation of the god in the form of a fish” (Dubois Hindu Manners Customs and Ceremonies.)

The fish was one of the emblems of royalty in India, Among the Hindus, the fish was regarded as a sacred animal. “One of the principal articles of the Hindu faith is that relating to the ten avatars or incarnations of Vishnu. The first and earliest is called the Matsya-avatar, that is the incarnation of the god in the form of a fish” (Dubois Hindu Manners Customs and Ceremonies.)

“The Matsya-Purana opens with an account of the matsya or fish . . . and deals with the creation, the royal dynasties, and the duties of the different orders,” ( Dutt. Civilization in Ancient India.)

A people called the Matsyas figure prominently in the wars of the Mahabharata, and the reigning family of Pandya claimed to be a branch of the Matsya-vansa; hence the origin of fish as the special emblem of the Pandyan Kings.

The Dravidian word for fish is Min. The Pandyan Kings of Madura took the title of Minavan or ” He of the Fish or Fisher”. The Pandyan tutelary goddess was Minakshi, the fish-eyed goddess ( of, the Roman goddess of wisdom, Minerva, and the Etruscan Minerva ), to whom a temple was built in Ceylon by Vijaya when he married a Pandyan princess. A coin of Devanampiyatissa, found at Tissamaharáma, bears the fish, torch, and trident. The fish (often in conjunction with the torch), occurs as a royal emblem on a series of rock inscriptions in Ceylon, described and deciphered at length by Neville in the Taprobanian, and by Parker in Ancient Ceylon. On one of these inscriptions, discovered at Lower Bintenne, the fish appears to be particularly complete, being clearly drawn, according to Neville, with ” pectoral and dorsal fin, tail, eye, and gill.”

“The use of the royal arms,” observes Neville, referring to the fish and torch emblems, “is unknown to me, to occur anywhere except in grants of the paramount reigning princes” (Taprobanian June, 1886).

The famous Stone Lion, from Polonnaruwa, now in the Colombo Museum, which formed part of the Lion Throne at Polonnaruwa, bears an inscription stating that the throne was built for Nissanka Malla, Lankeswara or Overlord of Ceylon, and terminating with the figure of a fish, in token of paramount royalty.

(12) The Sun-Flowers.

“The sun-flower was the badge of the royal house.” (E. W. Perera. Ancient Sinhalese Heraldry) The royal line belonged to the Suriyavansa “that royal race of the caste of the sun… none could inherit the empire of Ceilao except those that came directly from that caste. Of this caste came directly the princes whom the king of Cotta married to his daughter though he was poor and without a heritance” (De Couto).

“The sun-flower was the badge of the royal house.” (E. W. Perera. Ancient Sinhalese Heraldry) The royal line belonged to the Suriyavansa “that royal race of the caste of the sun… none could inherit the empire of Ceilao except those that came directly from that caste. Of this caste came directly the princes whom the king of Cotta married to his daughter though he was poor and without a heritance” (De Couto).

Surya (sun) occurs so frequently as a suffix in family-names. nearly exclusively the family-names of members of the Kaurava Vanse, that this suffix is at the present day practically

an indication of caste. Karave family names ending in Suriya range over the alphabet fromAbeysuriya to Wickramasuriya.

(13) The Sprigs.

![]() The significance of the leafed sprig on the Karáve flag is a matter for conjecture. I suggest that the sprig stands for the, wreath of margosa which Pandyan warriors wore around their heads when they went to war (Gazetteer of India: Madura District) or, more probably, the allusion is to the tradition preserved in the Janawansa, that Karáve soldiers accompanied Mahinda and Sanghamitta on their mission to Ceylon with a branch of the bo-tree at Buddhagaya.

The significance of the leafed sprig on the Karáve flag is a matter for conjecture. I suggest that the sprig stands for the, wreath of margosa which Pandyan warriors wore around their heads when they went to war (Gazetteer of India: Madura District) or, more probably, the allusion is to the tradition preserved in the Janawansa, that Karáve soldiers accompanied Mahinda and Sanghamitta on their mission to Ceylon with a branch of the bo-tree at Buddhagaya.

(14) The Lotus.

![]() The emblems on the flag appear on a ground semé with the lotus. “The lotus was the badge of the nation.” (E. W. Perera: Ancient Sinhalese Heraldry). The lotus is without doubt the most frequent motif in Eastern decorative art. It appears unceasingly in the art of Egypt, Assyria, and India, and was adopted also by the decorative artists of Etruria and Greece. In Egyptian art it was associated with the idea of immortality, in the Buddhist art of India with the idea of miraculous birth. It has been so highly and so variously charged with significance, and so frequently used, that in time it degenerated into cant, became devoid of symbolic meaning altogether, and is employed most often purely for decorative effect.

The emblems on the flag appear on a ground semé with the lotus. “The lotus was the badge of the nation.” (E. W. Perera: Ancient Sinhalese Heraldry). The lotus is without doubt the most frequent motif in Eastern decorative art. It appears unceasingly in the art of Egypt, Assyria, and India, and was adopted also by the decorative artists of Etruria and Greece. In Egyptian art it was associated with the idea of immortality, in the Buddhist art of India with the idea of miraculous birth. It has been so highly and so variously charged with significance, and so frequently used, that in time it degenerated into cant, became devoid of symbolic meaning altogether, and is employed most often purely for decorative effect.

Here remains to be considered the collective significance of the insignia of the Kaurava Vanse in the light of the history of this people in India and in Ceylon. One of the oldest traditions is recorded in a version of the Janavansa (see the Taprobanian: April 1886).

“After time had thus passed in the 207th year after our Buddha had gone to Nirwana, at the time when Devanipiyatissa Narendraya was reigning over Lakdiva, Dharmasoka Narapati of Dambadiva sending to Sri Lankaduipa together with the victorious Maha Bodin and the prince and princess Mahinda and Sanghamitta, archers employed. In bow-craft and people accustomed to fight with swords, javelins, pikes, shields and the like, who said, ‘ the pearl umbrellas, white canopies and chamara are our services – while the princes our kin are going it is not proper for us to stay’- forty-nine in number these also came for the Bo Mandala business…. Thus because princes who attained the kingship from time to time belonged to this race and attained it, Bhuwanekha Bahu on account of the dangers that arose from foreign enemies, bringing to this Lakdiva from the city Kanchipura, ninety-five of them in number, showed them royal kindness and established them there. From that time, keeping everything that was needed, appointing the five doers of service, he protected them.”

This statement in the Janavansa explains quite coherently the possession and use of the royal emblems by the Kaurava Vanse, confirmed as that statement is by the assertion of Barrados in. 1613 that these were royal symbols “which the former kings conceded to this race of people, that, being strangers, they should inhabit the’ coast of Ceilao.” Pridham represents the “five doers of service” as attached to the Kaurava Vanse, confirming the ancient tradition in this particular.

The Janavansa statement that ” princes who attained the kingship from time to time belonged to this race and attained it,” implies that the Karave people are Kshatriyas, and the concession of the royal symbols by the former kings, spoken of by Barrados, implies, in my opinion, not so much a bestowal of the symbols, as permission, in view of the strict local sumptuary laws, to use in Ceylon symbols to which Karave warriors were already entitled, identical emblems being used by kindred people in India.

I have already stated my reasons for believing that the use of the sun and moon emblems was the privilege of descent rather then the reward of merit. Neville speaks of the Makara as the special emblem of the Varnakula which like the Kurukula, is merely a clan of the Kaurava Vansa, in India as in Ceylon. The probability therefore is that the Makara flag, too, which tradition asserts was bestowed with the sun and moon flag by the king on the tribe, was really brought over by the clan to whom it belonged.

Members of the Varnakula, and the Kurukula (a Varnakula-thungen and a Kurukula-Naik) appear to have occupied the throne of Madura as late as the 12th century A. D. (Taylor Indian Hist. Mss. I. 201). It would seem that as late as the 17th century Karave chieftains ruled semi-independent principalities in South India (see Hunter “History of Indian Peoples,” for the independence of the S. Indian chiefs or nayiks of the 16th century); and some of the Karáve chiefs in South India were powerful enough even in the 17th century for the kings of Ceylon to value their assistance in war.

In 1618 when the “pugnacious Carias” (Pieris: Port: Era) of Ceylon were harassing Chankili, King of Jaffna, the king applied for assistance to the Naique of Tanjore, who sent to his assistance one of the pugnacious Carias of India, Varna Kulatta (i.e. Varnakula Adittá). “the chief of the Carias, the most warlike race in the Naique’s dominions” (De Queiroz). Two years later the same chief reappeared off the coast of Jaffna, again in a pugnacious mood; Faria Y Sousa referring to him as the “Chem Naique, that king of the Carias who had previously come to Chankili’s assistance.”

In 1656 while another Varnakula Aditta, Manoel d’Anderado, one of the pugnacious Carias of Ceylon, (whose full name was Varnakula Addita Arsa Nilaitte – a name borne also by Rowels, the Lowes, and the Tamels, Karáve families of Chilaw), was guarding the pass at Kalutara with his lascoreens, for the Dutch against the King’s troops, the King Rájasinha, on his side made overtures for assistance to one of the pugnacious Carias of India – the Patangatin of Coquielle (Baldaeus). Two years later, the same Manuel D’Anderado “signalized himself before Jaffnapatam” (Baldaeus). These incidents of the 17th century symbolize in epitome the history of the Karáve people in previous centuries, from the legendary days of the despatch by a Cholian King of an expedition “under a Kurukula captain” to obtain snake-gems from Ceylon for Kanakai, the bride of Kovalan, to the most recent times. From the 6th to the 8th century, when, according to the historian Dharma Kirtti, Ceylon was in the throes of civil war, three rival houses contending for the throne, each importing numbers of soldiers from S. India, Kurukula and Varnakula captains and men must have been in great demand.

By the end of the 8th century, Ceylon was full of these “Demillos” demanding the highest offices in the state, and apparently getting them, the Sinhalese being too weak to resist. In the 12th century it was a chief named Aditta, (Bell: Kegalla Report, p. 74), a Tamil Commander of high rank in the army, who led a great naval expedition to Burmah, when the coast of Ceylon “was like one great workshop, busied with the constant building of ships”. There can be little doubt that it was Karáve men who manned this expedition, the Sinhalese though an island race, being strangely averse to sea-faring.

Two centuries later an expedition led by Karave chieftains from the Coromandel coast rescued the fort of Puttalam for the Sinhalese King. Two centuries later, on the Sinhalese King’s conversion to Christianity, he appears to have relied on Karáve soldiers for the security of his throne. The pescodores or “fishermen” are very prominent in the stirring times of the Portuguese, fighting on one side or the other, or on both by turns. One pescador by his “skill in war” on the royal side rose to be Prince of Uva and a regent of the kingdom. (See Baldaeus for the text of the royal, patent of 1613 appointing Kuruvita-rála, Prince of Uva, a Regent, the King on his death-bed ordering all the estates of the realm to take the oath of allegiance to the two Regents till the Crown Prince came of age and “to show them the same respect as to our own person”).

A number of Karáve ge names which have come down from these times indicate their owners’ military occupation at this period, such as Totahewage, Guardiahewage, Guardiawasan, Marakkalahewage, Hewakodikarage etc.

In Dutch times, the Karáve people stubbornly remaining Catholic, were not in favour, and their honours and privileges were curtailed. But Dutch governors still instructed their lieutenants’ that “the Carias… being the most courageous, are to be employed for all purposes of war,” and some descendants of the earlier chieftains, such as the Anderados, the de Fonsekas, and the Rowels, continued to remain in power and prominence.

In British times there has been no fighting in Ceylon, but the Karave people continues to give evidence of possessing what Hunter describes as “the Inexhaustible vitality of the military races of India.”

It will be noticed that most of the Portuguese writers (De Queiroz, Barrados, etc.) and some Sinhalese writers, speak of the Karave people as a race. And it will be evident that the Kaurava Vanse, strictly speaking, is not so much a caste as a tribe, consisting, as we have seen, of a number of clans. Dr. Paul Pieris has drawn attention to one of the tribal characteristics of the Karave people – its tendency, even at the present day, “to act as a corporate whole”. My view of the Karave flag is that it is a tribal flag, its royal emblems indicating the Kshatriya origin of the tribe. But if, as Mr. E. W. Perera seems to suggest, the flag is indicative of occupation on a caste basis, the only occupation Indicated by the emblems on this flag is the occupation of the Kshatriyas or Warriors.

Notes:

- The flag analyzed by the author in this article is based on one found in Mr. E. W. Perera’s monograph on Sinhalese Banners and Standards.

- The original article published in 1921 does not contain any photographs or drawings, but an extract available with the family contained a Black & White photograph of the above flag (Red color image).

- A Color photograph taken from the book ”Sri Lanka Flags’ – unique Memorials of Heraldry, 1980, Edited and Published by Edith M. G. Fernando has been inserted to make the composition of the flag more clearer to the reader, and to indicate the different