Patabendigé Kings, Rulers and Sub Kings.

This article by Raaj de SIlva explores the role of Patangatims and the ‘Ge’ name of Patabandige.

Left: An old etching of King Rajasinghe and his court. Note the similarity of the royal symbols carried by the courtiers with those on the flag above. Of particular interest are the two pearl umbrellas, the sun and moon symbols, alavattam ceremonial sun shades and the conch shield

Patabändigé (also referred to as Patangatim, Pattangatti, Pattankatti in historical sources) is one of the most prevalent gé names among the Karava race of Sri Lanka. It is an exclusively Karava name.

History

Ancient period

Pattalattanan in Tamil had meant a consecrated king according to the Tamil dictionary Yálpana Periyakarádi (655 & 656). Taylor too translates Pattangatti as ‘crowned’ (Taylor 1835) which obviously means a King or a sub king. In ancient India too Patta and Pattâvali (note phonetic similarity to Patabëndi ) had meant ‘titles of honour’ (South Indian inscriptions I.159 fn.1. Indian Antiquities XI.245 fn.)

As shown above, it was not the crown but the forehead-plate that was part of a Sri Lankan king’s regalia, the five insignia of royalty (pancha kakudha bhanda). As such the tying of the forehead-plate was the Sri Lankan equivalent of European coronations. The great chronicle of Sri Lanka, the Mahavamsa, calls the royal inauguration ceremony Pattabanda Mahothsava (The ceremony of tying the forehead-plate). In Chapter 67, verse 91 the Mahavamsa describes how King Parakramabahu the great was inaugurated by tying the forehead-plate (Mahavamsa 67.91) This practice appears to have continued right upto the end of the Sri Lankan royal line as John Davy describes the installation of a Kandyan Monarch in the same way (Davy 1821.123)

Mediaeval period

King Sahasamalla (AD. 1200 -1202 ), and Parakramabahu the Great were prominent among the many Sri Lankan kings who used the fish emblem ( a recurring emblem on Karava Heraldry ), on their stone inscriptions. An inscription of King Sahasamalla refers to the appointment of a Commander-in-chief cum Prime Minister as “senevirat patabandavá agra mantri kota” (EZ II.222 – 224 ). The 15th century Ummagga Jataka too narrates the practice of honouring military commanders with forehead plates as: “Senevirat patabandá” -Invested with the rank of Commander-in-chief (Ummagga Jataka 29.160). The Kavyasekaraya refers to such individuals as ‘isa sevulu bändi’ ( Kavyasekharaya XIV.64. EZ I.240 n3) The 16th century Gadaladeniya inscription (EZ IV.23) too shows that honouring a person was referred to as ‘patabändavíma’.

Kotte period

The Rajavaliya narrates that when King Vijayabáhu VII (AD 1528 -1529) of Kotte was conspiring to kill his sons, the three princes escaped from their Father’s kingdom through the Kauravadhipathi gate and went to a Patabenda’s house in Jaffna. Later,one of the princes, Máyadunne, left the other two princes, Bhuvanekabahu and Raigam Bandára with the Patabenda (who is also referred to as Kauravadhipathi), and went to Kandy to seek assistance from Jayaweera Bandára who was married to his cousin, a Keerawella princess. (Rajavaliya 225) This illustrates the interconnectedness of the Karava Patabendas of the period. They were from same same Surya wansa clan (Solar dynasty) as the ruling families.

The Portuguese who arrived in Sri Lanka in the early 16th century described the Patabändas / Patangatims at the time of their arrival as “Kinglets (subkings) of the Karávas who controlled not only one village but sometimes the whole coast as a master or ruler” (Valignano 1577. Perniola 82). Other Portuguese writers, Joaõ de Barrows (1520) and Castan Heda (1528), refer to five Kings stationed at important coastal towns, their ears laden with jewels and claiming relationship with the King of Kotte. (Ferguson 1506, JRASCB XIX.283 -400) These five kings were evidently the Patabändas, the Kinglets of the Karávas referred to by others.

King John III of Portugal says the following in his letter of 20th March 1557 to his guardian of the religious order: “I am much pleased to rejoice at the news you give me of how our lord has been pleased through the agency of the members of your order to illuminate the Nation of the Carias who you say live in the ports of Ceylon, and are said to exceed 70,000 souls, whose captain named Patangatim accompanied them” (Queyroz 327).

The Portuguese historian Fr. Queyroz describes an early Portuguese battle in Sri Lanka as follows: “At that time the Kinglet of the Careas appeared with the whole might of that kingdom which exceeded 20,000…...” (Queyroz 631). Valentyn too notes that the chiefs of Sri Lanka were from among the Karávas (Valentyn 1726). During this period, Chem Nayque and other Karavas were the Naval commanders of the Nayaks of Tanjore (Queyroz, 638). But in addition to manning the Navy, the Karavas appear to have also been engaged in trading. For example the Patangatim of Mannar had been responsible in the early 1600s for arranging the sale of pearls in the Nayaks’ territory in India. (Pieris The Kingdom of Jaffnapatnam )

It should be noted here that the early Portuguese historians refer to the Patabändas as Kinglets, meaning sub-kings, and not as mere chiefs as they later came to be referred to after a century of European rule.

Portuguese period

When the Kotte kingdom was ceded to the Portuguese by the ‘Malvána convention’ in AD.1597, at least one of the three local nobles who signed the agreement on behalf of the Sinhalese is mentioned as a Karava Patabënda . Portuguese nobles who were known as Fidalgos signed it on behalf of the Portuguese king. The three local nobles had been selected by a council of nobles and people (Ribeiro 95) and confirm the regal status of the Patabendas of tthe 16th century.

The ‘Nallur convention’ of 1591 ceding the kingdom of Jaffna to the Portuguese was also signed by Karava nobles.

The Portuguese Tombos from the period show that the Patabendas did not pay any taxes on their land, ships or other assets as they continued to be regarded even by the Portuguese as independent rulers.

Jesuit annual letter of 29/12/1606 from Cochin states that the early Portuguese missionaries first concentrated on converting the Karava Patabändas as they were the leaders and rulers of the people. They were used as examples for other gentiles to follow (Perniola II.254) The Portuguese have documented many instances where hundreds of others converted, following the Patabända’s conversion (Perera. C.A. & L. R. 1916 II.24).

The European invaders as well as Sri Lankan Kings had approached the Patabändas for assistance in wars. As a result the Mahapatabëndá of Colombo was beheaded and quartered by the Portuguese in 1574 for treasonable communication with King Mayadunne (AD 1535 – 1581) of Sítáwake (Queyroz 424). In AD 1656 the Patabända of Coquille (Koggala) was approached by King Rajasingha II (AD 1635 – 1687) of Kandy for assistance (Pieris Portuguese Era II.454)

The principal kinglets were the Mahapatabëndás who were referred to as Patamgatim Major and Patamgatim Mor by the Portuguese. Two of the Mahapatabëndás of Negombo in 1613 were: Kurukulasuriya Dom Gaspar da Cruz and Varnakulasuriya Afonco Perera (Raghavan, 1961.33. The Portuguese Tombo of 1615 which deals with the ports, villages and lands on the coast from Puttalam to Dondra, lists the chiefs of each village along with their land holdings, crops and revenue. It is noteworthy that the chiefs of most coastal villages which included Negombo , Chilaw , Kammmala, Kalutara, Maggona and Donrda were Patabëndás(Pieris Ceylon Littoral)

According to Philip Baldaeus Dona Catherina, the sole heiress of the Kandyan kingdom was also a Patabenda and bore the name Maha Bëndigé (Baldaeus VIII.681).

Baldaeus also refers to two other Patabëndigé princesses, Malabanda Wandige and Rokech Wandige (Baldaeus I) and the Patabëndigé vice-admiral Wandige Nay Hanni who was a nephew of the Karáva Prince of Uva, Kuruvita Rala (Baldaeus XIII.668 & 692).

Dutch & British periods

The Portuguese diminished the position of the Patabendas from Sub-kings to chiefs but the Portuguese Tombos (official state records) of 1613 still rank the Patabendas above the Mayóráls (Pieris Ceylon Littoral.26). The Mayóráls were the local equivalent of European city mayors. The Dutch who succeeded the Portuguese, stripped most of the Karávas of their powerful official positions as they suspected the Karávas to be more loyal to the Kshatriya kings of Kandy or to the Portuguese whose religion many of the Karávas professed.

The Dutch elevated persons of mixed origins to replace the traditional Karáva chiefs and many such families of mixed origin appear to have identified themselves with the Govi caste as they could not be accommodated within any of the other castes. (See Sri Lankan Mudaliyars ). Disfavoured by the Dutch, the position of the Patabëndás dropped sharply to the level of a Muhandiram during the 18th century Dutch period (Raghavan, 1961.42. JRASCB.XXXI.No. 83.448).

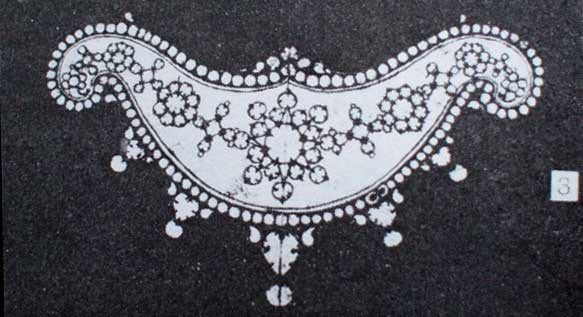

We know that the forehead-plate continued to denote nobility even as late as the beginning of the Dutch period as a Dutch envoy of 1612 refers to the ‘gold headband of a Sinhala dignitary’ (JRASCB.XXXVII 1946 No.102.49). The A.D. 1691 tombstone of Patangatim Francisco Piris’ wife from St. Thomas Church, Jinthupitiya illustrated here, shows that the Karava heraldic symbols: Pearl umbrella, Palm tree, caparisoned Elephant and Fish symbol were used even on their tombstones to denote their status.(JRASCB XXII 387)

A few of the Patabändas who figure in the late Dutch period tombos are: Chikoe Patabändigé Thome Silva Kurukulasuriya, Pattangatyn of Kalutara, A. D. 1760; Mahabadugé Jasientoe Fernando Kurukula Jayasuriya, joint Pattangattyn of Barberyn. A. D. 1759; Bastian Pieris Rasa Manukula Warnakula Ditadipadicear, joint Pattangattyn of Colombo, A. D. 1761; Steeven Fernando Weerawarna Kurukulasuriya, Pattangattyn over the Rue Grande (Grand Street, Negombo), A. D. 1763; Luis Fernando Varuna Kurukula Áditya Adapannár. Pattangattyn of Colombo, A. D. 1769 (Ceylon Dutch Records: 785/120, 785/543, 2284/91, 2443/75 and 1034/607. Raghavan 1961.44 & 45). In 1762 the Dutch refer to the Basnáyaka of Devundara as Bandáranáike Suriya Pattangatyn (Secret minutes of the Dutch political Council, Wednesday 22nd September 1762) Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe (AD. 1798 – 1815) the last king of Kandy, is also described as a Pattangattyn in a South Indian source (Taylor 1835 Kuruksetra II.26).

The gradual displacement of the traditional Patabëndigé rulers and sub-kings of Sri Lanka during the colonial period is clearly evident in contemporary colonial records. The Patabëndas who figured prominently in early Portuguese records as kinglets, are reduced to chiefs by the end of the Portuguese era. They fade away gradually during the Dutch period and are hardly mentioned during the British period. See Timeline of the Karavas.

Current usage

Some of the Patabendige ancestral family names still used only by Karava families of Sri Lanka are:

| Abeydíra Gunaratne Patabändigé Abeysúriya Patabändigé Abeyavarna Patabändigé Abeydíra Viravaruna Patabändigé Alut Patabändigé, Arketti Patabändigé Árukutti Patabändigé Abedíra Jayawickrama Liyana Patabändigé Asuramána Patabändigé Bála Patabändigé Chandiram Patabändigé Colomba Patabändigé Colomba Mahá Patabändigé Edirivíra Jayasúriya Liyana Patabändigé Edirivíra Jayasékera Kurundu Patabändigé Edirivíra Patabändigé Ediriwickremasúriya Patabändigé Gikiyana Patabändigé Gintota Sarukkala Patabändigé Gunasekera Árachchi Patabändigé Hettiyá Patabändigé Ingiri Mahá Patabändigé Jayasekera Patabändigé Jasenthu Patabändigé Jayawardhana Sembukutti Patabändigé Jayawickrema Patabändigé Jayavira Liyana Patabändigé Jayawarna Patabändigé |

Hátagala Patabändigé Kahakachchi Patabändigé Kálingapura Patabändigé Kalutara Patabändigé Kánchipura Patabändigé Káriya Karavana Mahá Patabändigé Káriyawasam Patabändigé Kodippili Patabändigé Kosma Patabändigé Kotte Patabändigé Kumára Patabändigé Kurana PatabändigéKurukulasuriya Patabändigé Kalutantri Patabändigé Mututantri Patabändigé Mahá Patabändigé Madduma Patabändigé Loku Patabändigé Lamábadu Varnakulasúriya Patabändigé Manampéri Mahá Patabendirálalágé Maha Marakkala Patabändigé Módera Patabändigé Mahá Nátha Patabändigé Málamí Patabändigé Mathangavíra Patabändigé Moratu Patabändigé Nilavíra Patabändigé Nágasúriya Kumára Patabändigé |

Panchashíla Patabändigé Patabëndi MaddumágéPatabendi Maha Vidánagé Penkutti Patabändigé Podi Marakkala PatabändigéRajapaksa Patabändigé Ran Patabändigé Rana Patabändigé Ranavíra Patabändigé Rénda Patabändigé Ratnavíra Patabändigé Samarakon Patabändigé Sinhapura Patabändigé Súriya Patabändigé Vijayapura Patabändigé Vijesekera Patabändigé Vijesuriya Patabendi Muhandiramgé Varunakulasuriya Patabändigé Varnasuriya Patabändigé Veeraratna Jayasúriya Árachchi Patabändigé Veerawarna Patabändigé Vira Konda Patabändigé Vitárana Patabändigé Weerakon Patabändigé Weerasuriya Patabändigé Wickremasuriya Patabändigé Wickrema Kodippili Patabändigé Wijayanáyaka Patabändigé Wijeweera Patabändigé Yápané Patabändigé |

Raaj de Silva

This article can be also found in the www.karava.org website.

References:

Baldaeus Philip 1672, Translation of 1703 A Description of Ceylon

Ceylon Dutch Records, National Archives, Colombo, Sri Lanka

Davy John 1821 An Account of the Interior of Ceylon and of its Inhabitants with travels in that Island

EZ (Epigraphia Zeylanica) Colombo Museum Vols. I , II & IV

Ferguson Donald The Discovery of Ceylon by the Portuguese in 1506,

JRASCB (The Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society)

Mahavamsa, Geiger translation

Paranavitana S Sigiri Graffiti Volume II

Perera Fr. S. G. The Jesuits in Ceylon C.A. & L. R., vol. II, 1916

Perniola Fr. S. J. The History of the Catholic Church – Portuguese period

Pieris P. E. Ceylon the Portuguese Era, Vol. II

Pieris P. E. edition of The Ceylon Littoral, A.D. 1593

Pieris P. E. edition of The Kingdom of Jaffnapatnam A.D. 1645

Pújávaliya, Rev. Gnanananda edition

Queyroz Fr. S. J. 1688 The Temporal and Spiritual Conquest of Ceylaö

Raghavan M. D. 1961 The Karáva of Ceylon,

Rajavaliya, 1997 Suraweera A. V. edition

Ribeiro Ribeiro’s History of Ceiláo

Secret minutes of the Dutch political Council, 1762 Colombo Museum

Taylor W. 1835 Indian Historical Manuscripts quoted in Kurukshetra, vol II, page 26

Ummagga Jataka 1978 Educational Publiations Department, Sri Lanka

Valentyn Francois – Mitsgaders een wydluftige Landbeschryving van’t Eyland Ceylon etc. Joannes van Braam Amsterdam 1726 quoted in Kurushetra II.26

Valignano S. J. Malacca 1577. A Summary report on India November 22nd to December 8th