THE GENIUS OF GILBERT KEITH CHESTERTON

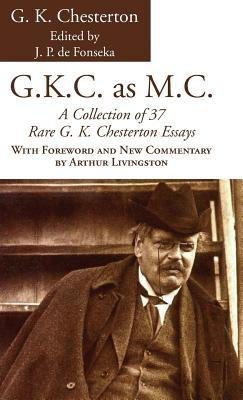

A Review of “G. K. C. as M. C.” edited by J. P. de Fonseka.

By EDMUND J. COORAY. (From the Blue and White 1948)

Mr. R. A. G. GARDINER has said: “No clamour, no book” is Mr. Chesterton’s motto, as far as new books are concerned.” That was said twenty years ago but he’d be a bold man who would tell C. K. C., that he has” progressed” since then. Ere he could finish the sentence, he would – (as Mr. de Fonseks says) – ” feel the tremor of a mountain flying shrieking, or even more dangerous, advancing against him.” No: it is safer to believe that “No clamour, no book” still holds good. Besides, it is not particularly difficult to guess who has clamoured for this latest” Chestertonic.” ” It is my friend,” writes G. K. C. in the dedication, ‘ whose excess of enthusiasm has inspired this collection.” Mr. de Fonseka has put all Chestertonians – nay, all lovers of English literature under a permanent debt, by bringing together or the first time some of these ” prefaces to which other people have fervently contributed books.”

They range over a period of nearly 30 years and the topics discussed vary from detective stories to drinking songs and from theological pamphlets to the literary classics. ” I hope” writes G. K. C.” the bundle will serve to show that my taste was catholic with that small ” c ” that is considered more important than a large one. Some of them were written long ago when some of my views were not fully formulated, but on the whole I am rather surprised to see how little my fundamental convictions have changed. For my final conviction, which was also a conversion, did not come to destroy but to fulfill.

The book is an orgy of good things. Here you get the account of G. K. C’s first meeting with Belloc, which will positively intrigue admirers of that noble quadruped known as “Chester.Belloc”; then there is an essay, on Cobbett, “the noblest English example of the noble calling of the agitator, an essay on his brother Cecil Chesterton with whom he never quarreled because they always argued; then an introduction to “Grand mamma’s book of Rhymes” published by the Oxford University, an introduction to a book of drinking songs which are ” songs that can really be sung because I have sung them myself and a more complete proof of the contagion of melody cool not be found,” a rollicking not to say uproarious introduction to the Catholic Who’s Who”:- “A man who consults a work of reference is generally a man in a hurry. A man who reads an introduction to a work of reference is always a man of unusual and almost unnatural leisure – a man whose leisure has developed into devouring tedium, and whose tedium has reached the point of desperation and recklessness. He must have collected and studied stray scraps of newspaper; he must have read carefully everything printed on his railway ticket; he must have read Bradshaw and Mrs. Eddy and every last hope of a desperate reader before he falls back on the introduction to a directory. I cannot remember that I ever met a man who had read the introduction to any such book as” Who’s Who.” Certainly it never occurred to me to read it and it is only through the desire of others that it occurs to me to write it. But I am at least comforted by this reflection that not many people are likely to read it.”

Then there is an essay that should have been entitled “The Innocence of H. G. Wells”. Mr. Wells is so charmingly innocent when he talks of his Utopia, where Humanitarianism is the order of the day and where men spontaneously rush into one another’s arms; in reality, they are more likely to rush at one another’s throats. The inhabitant of the Wellsian Utopia is supposed to fall in love with his neighbour it first sight. The sober truth is that he will fall in love with everyone except his neighbour. In short there is only one thing in the way of the Humanitarian – and that is the human being. Chesterton clinches the argument in one brilliant paradox:-” Ordinary men find it difficult to love ordinary men – at least in an ordinary way. But ordinary men can love the lover of ordinary men who loves them in an extra ordinary way. For instance it may be difficult to get a fat burgess and a fierce hungry robber to love each other, but it is much easier to get them both to love St. Francis of Assisi. And what is true of St. Francis is more true of his Divine Model. Men can admire perfect charity before they can practice even imperfect charity and that is by far the most practical way of getting them to practice it.”

There is one preface which stands entirely apart from the rest. In its sweet simplicity it no merits comparison with Dr. Johnson’s famous letter to the little daughter of Bennett Langton, written large and round that the child may read. It is a letter written by Chesterton to his little god-daughter in Germany – four pages literally overflowing with the milk of godfatherly kindness. Chesterton pleads guilty to the charge of having played ” Father Christmas ” once at a children’s party, but urges in mitigation of sentence that on that occasion Father Christmas was much too fat to get down the chimney. And it ends on this note of birdlike exquisiteness:- ” When little things like you and me are one year we are so nice that people would give us anything. The great question is Barbara, can we keep as nice as that”?

There is one preface which stands entirely apart from the rest. In its sweet simplicity it no merits comparison with Dr. Johnson’s famous letter to the little daughter of Bennett Langton, written large and round that the child may read. It is a letter written by Chesterton to his little god-daughter in Germany – four pages literally overflowing with the milk of godfatherly kindness. Chesterton pleads guilty to the charge of having played ” Father Christmas ” once at a children’s party, but urges in mitigation of sentence that on that occasion Father Christmas was much too fat to get down the chimney. And it ends on this note of birdlike exquisiteness:- ” When little things like you and me are one year we are so nice that people would give us anything. The great question is Barbara, can we keep as nice as that”?

The last paper in the series is that immortal first article of ” G. K’s Weekly” in which Chesterton explains why “as a variant on the popular advice to give a dog a bad name and hang him,” he proposes to “give this piper an exceedingly bad name and hang on to it.”

This collection of prefaces is richer by Mr. de Fonseka’s ” Preface to Prefaces” – a thing pressed down and running over with wit and wisdom. There is some discerning criticism of Chesterton and Chestertonism, but its very scantiness foreshadows better things to come. Towards the end Mr. de Fonseka becomes almost alarmingly gloomy as he ponders over the calamities that might have befallen us but haven’t. He writes: ‘In a Bolshevik order, there could be no letter written to a god child, because there would be no God. The Grandmamma who wrote moral rhymes for children would probably be summoned before the Ogpu for corrupting youth with morality. In the Pussyfoot scheme of the world there would he no singing of the songs of the tap, if a man may not even say when; and another form of society would have banned the immoral and complex word veal and ham-pie, because the world had become at heart very very Vegetarian.” Indeed I admit all this is very depressing; but was it not the Ungloomy Dean who once said ” The worst troubles of my life are those that never happened”?

EDMUND J. COORAY.

“G. K. C. as M. C.” – Selected and edited by J. P. de Fonseka. Published by Methuen and Co. 36 Essex St. London W. C. 7s 6d. Order through local booksellers.