When I say that Belloc is ours I mean that, leaving aside for the moment the clear title of the common Mother of Humanity, the Church, Belloc is mine and yours and the Empire’s and John Bull’s and Fleet Street’s and Grub Street’s and France’s. Beyond these excellent institutions, a large miscellany of nondescript persons and popular philosophers have also claim to the estate aforesaid. Nay, I have even heard the infinite snobbery of our time speak patronisingly of “Belloc, don’t you know” and have once or twice seen him out in drawing-rooms as a token of literary taste. From this habitation, I fancy, Belloc may now and again go for a holiday upcountry or on an impromptu picnic or alleviate the fatigue of a capitalist owner going inland to visit an estate. Further I have met a great lady who had really taken up the book called On Everything, expecting to find therein an elucidation of all the doubts and problems that harassed her life, and had even written her name on the copy. Then again. I have, on other occasions, met Belloc on the railway at odd places and times, coming out of the pocket of a literary gentleman with a blue pencil and an eye to paradoxes; or squeezed between the newspapers of a fresher who wishes to know “who is this Belloc they are speaking of” or stowed away on a hat-rack in mixed company or even performing the office of a fan. On one particular occasion the discovery that Belloc travelled in the train was not altogether so easy, for the gentleman sat at the far end, wearing an inhospitable look, with the book cased in a wrapper; and it was only a very clever piece of reading, spelling backwards, that disclosed Belloc to a gratified admirer on that occasion.

Not the less happy has been my meeting with Belloc as a permanent possession in those asylums of the hungry, we call libraries. Here, the appetite is acutely sharpened by the plenitude of Belloc, present in many volumes, all betraying signs of other people’s feasting: Belloc dog-eared; Belloc with broken limbs; Belloc faded, spotted, mouldy; Belloc thumbed; Belloc scored black and blue; Belloc commented on the margins; Belloc dusty; Belloc shining; Belloc with the author’s portrait cut out; Belloc drawn and scribbled on; Belloc spoiled; Belloc ruined; Belloc numbered; Belloc stamped; Belloc catalogued; Belloc registered in a ledger. And thus, by the tender bequests of those paternal testators like Mr. Constable or Mr. Foulis or Messrs. George Allen and Unwin or Messrs, Chatto and Windus or Mr. John Lane or Messrs. Methuens most of all, the library browser, and the man in the train and the great lady and the capitalist owner and the infinite modern snobbery and John Bull and you and I, — we have all succeeded to the inheritance and exercised our rights. To despatch the matter, we all own Belloc without let or hindrance.

But, although this is so, to use the noble phrase of Bottom the Weaver, a man’s but an ass if he go about to expound that all the legion of us cherish Belloc for precisely the same reason. Indeed, it would be safer far to say that the legion of us have as many reasons in the matter. A young lady of my acquaintance, for instance, ever since a memorable day has treated Belloc as a bringer of victory, a controversial pere de victoire, a sort of argumentative cudgel that deals the coup de grace. For, one casual day, having engaged her dad, a business man in the town on some point, I believe, of routine, she had chanced to cite an opinion from Belloc; and the foe was instantly routed and she remained master of the field. The Oxford Union Society, it seems to me, would have much the same attitude to Belloc in the matter of his undergraduate oratory in debate, in which, a recent writer says, he coruscated brilliantly.’ Then, Mr. A. St. John Adcoek among us cherishes Belloc as one of the ‘Gods of Modern Grub Street’; and those of us who indite our pennyalinerisms may supplicate the divinity called the “Editor of the English Life” in respect of the three guineas he dispenses for a thousand words. Mr. A. G. Gardiner on the other hand, cherishes Belloc from a social standpoint, because Belloc is a ‘Pillar of Society’; while Mr. Bernard Shaw does so from a ‘zoological’ standpoint, because Belloc represents the hind portion of an unique quadruped called the ‘Chester-belloc,’ just now the most dangerous animal in England. Further, any ordinary democrat among our number would for ever remember that Belloc has made one of the most vigorous defences of private property put forward in modern times; while any common monarchist would go mad to read in Belloc that ‘monarchy must come,’ quite a different thing from ‘monarchy must go.’ Yet further, a capitalist among us will open his arms to Belloc for having urged the sheer necessity of capitalistic wealth; while any proletarian worker will embrace Belloc for having averted, as far as a book of Belloc could, the slavery of Industrial Socialism.

Then, there is a series of other equally pertinent claims, Mr. Asquith would claim Belloc for Liberalism; France would claim Belloc as a Frenchman; John Bull would put in a counterclaim for Belloc as a domiciled Englishman; Hansard would claim Belloc for the House of Commons, wherein he sat four years (though, going out, he condemned Parliament summarily); the heart of a Balliol Scholar would thrill at the resplendence of his fellow collegian in the Honour History School; an Athletic Corporation would gladly point out that brains and riding and swimming can go together: a French Patriot would utter his most polished encomium on Belloc’s Paris; a French Royalist would cry over Marie Antionette; a French Republican Extremist would sing the Red Flag brandishing Belloc’s Danton and Robespierre; the French Minister de Guerre would gratefully certify that Belloc served his term; our English Minister of War would make a note of Belloc’s Warfare in England; our Army Council would perhaps study on the sly Belloc’s expositions of the strategy of Malplaquet and Oudenarde; the Commissioner of Public Works would dissect the principles of road-making underlying Belloc’s Old Road; an artist would be green with envy at the author’s own illustrations in the Path to Rome; the mouth of Lombard Street would really water at the money-making in the Mercy of Allah; a vagabond would sit in a Pyrennean inn and imbibe hop ale and the Hills and the Sea; Mr. H. G. Wells would be surprised at the result of mixing the Romance and Teutonic civilizations; Dr. Marie Stopes would make out a case for the Eugenics of blending races. And these, and a medley of other considerations would make up the whole and wherefore why the legion of us hold to our inheritance of Belloc and would never dream of alienating it.

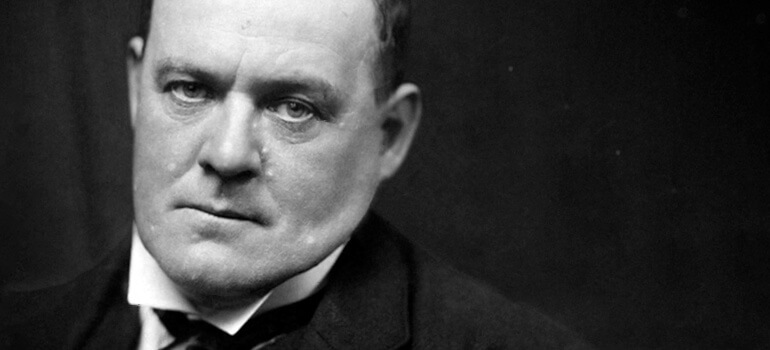

But my own claim (and perhaps yours) has to be stated differently. It was indeed in a very distant apocalyptic vision that the spacious form of Belloc first crossed my path, and left me regarding that Falstaffian girth with genuine fraternal feelings. In those days Belloc loomed large in the world through the good offices of Messrs. Methuens as a very perfect gentle essayist. And the essayist of our time is not a mere ordinary scribe, but a great combination of the transcendental capacities of prophet or moralist or philosopher or humourist; and Belloc the essayist did really find room for prophecy or morals or philosophy in many worthy places and things such as an empty house, a barber, an onion-eater, cheeses, a lunatic, a man and a dog also, them (cats) and in taking up one’s pen, and a great many others, which he later collected under the ominous titles of On Nothing On Everything: On Something; On This and That and the Other. Never had any essayist performed these miracles, not Addison, not the great Johnson, not Macaulay. And the series went on until the process of mystification went its furthest, and the latest essay-craft of Belloc had to be labelled simply On.

Personally, it is the elaboration of this category that I should always think Belloc’s mission to consist in, in helping to solve the problematic profundity of ordinary and familiar objects, to unravel the mystery in a pork-pie or the deep philosophy of a cigar-stump, to utter a prophecy in respect of bobbed hair or a moralisation on a top hat; that is to say, to explain the fundamental aspects of the common-place and the simple, which is after all not a simple or easy matter at all. In this sense Belloc would tell us more pertinent things about the essence of a match-stick than about the French Revolution; and more pertinent things about the history and civilization characterising a coin than about the history and civilization, distinguishing the Jewish Race. In such a study we may even learn the comparatively trivial fact that the match-stick played some part in furthering a little disturbance called the French Revolution, or that the coin played some part in moulding the dubious position of a people called the Jews. And from two instances of Belloc’s latest, I find Belloc still practises the art. The one, a cutting essay with deep indignation pronounced the doom of that quaint medicine that quickens our humdrum lives, the novel. The old novel was the work of supreme artists, called forth by the pleasure in it, by the satisfaction of writing for its own sake. The new novel was the work of asinine people pouted out for vendors to impose on the gullible as ‘best-sellers.’ And the novel was doomed; but a rousing circumstance lay in the fact that Belloc himself has penned some six of these very handy commodities called The Green Over-coat, Emmanuel Burden and so on, and I should have been greatly edified did I read a publisher’s list announcing a new novel by Belloc this season. The other instance, a very genuine scintillation, how Belloc would manage conversation in trains, how make the tongue-tied blubber and the chatterer subside, Belloc always with serene humility and meekness of heart getting the better of the other fellow. But the art is a useful one for us train-travellers, proud of our locomotive method, for the course of true modern progress is a railway train, and Belloc himself had come to most of us in a train.

In this way the legion of us hold Belloc. But among us there is one claim outstanding and pre-eminent, and that is the most momentous and significant thing in all Belloc, the claim of the Church or the Faith. In this respect, Belloc at once takes his place among a great lay apostolate that have; presented the Faith to the multitude, or preserved it many a time against later and newer, academic and intellectual Vandals. I should not like to ask as to how many Belloc gave the Faith to, but this much is known, and even the right hand has failed to keep the left in the dark that Belloc gave the Faith to Chesterton: and in respect of this I should well make every essay on Belloc a part of an essay on Chesterton or vice versa, whatever Mr. Adcock would say. And the distinctive mark of Mr. Shaw’s biological specimen of the ‘Chester-belloc’ would, therefore, be simply a spiritual community in the tradition of this Faith. Now, the historical basis of this community between two persons, or what is still the same thing, the millions inhabiting Europe, Belloc puts m some such way as follows : “The life of Europe is her civilization. This civilization was formed through, exists by, is consonant to and will stand only in the mould of the Church; that is, it was built by and on the Faith. Europe, suffering from her attempt at the ship-wreck of both this Faith and this civilization, at different times\ must go back to the Church, or she will perish, for ‘the Faith is Europe and Europe is the Faith;”

And Belloc, in that brilliant book, Europe and the Faith, a sublimer, newer, more pregnant Path to Rome, as in other works, in casual digressions and stray sentences has kept making that noble gesture, that recently melted the world into goodwill at Malines, but it is a forgone conclusion that the gesture, productive though it be of much concord, must yet displease in sundry places, just as much as many of the other poignant, categorical, provocative things in Belloc must be verily a sign that shall be contradicted. And the phenomena of dissent would appear in the heavens. Accordingly, the Dean of St. Paul’s, I fancy, would regard with unmixed vexation the whole performance entitled Europe and the Faith; a National Religionist would obliterate the first portion of the title; a Modern Rationalist would delete the second half; a New Theologian will put a question-mark; a Modern Evolutionist would laugh to scorn the orthodox cosmology in First and Last; a Promoter of the English-Speaking Alliance would flare up at the Contrast for imperilling the American Friendship; an Aristocratic Diehard would curse the House of Commons: a Marxian Collectivist would tear up the Servile State; a Pacificist would execrate the pugnacity of the Eye Witness; a Eugenist would pooh-pooh things passim; a Higher Critic would put on his clorophyll spectacles; a Vegetarian Society would object to the veal-cutlets in Belloc’s books; a Temperance Union, to the beer; all the Jews uniting into a symbolic Shylock would cry to hoarseness ‘He hates our sacred nation and a mere man whom I met in a train in the dark days of the war, when one of those brilliant forecasts of the war Belloc made in Land and Water had gone another way, would call Belloc a fool. Belloc, really, is that sort of genius.

Meanwhile, the choice, legion of us comprising you and me and other excellent persons, we shall keep Belloc as the embodiment of the ordinary sanity of human beings, full of interest in many matters and full of the benevolence, laughter, wisdom, the fine scorn and happy irony of our nature. And let Belloc still interpret the principle of life with that brightness and solidity, which even a tempting vulgar pun on his name discloses. Let him keep that character, that Belloc personality that has been the most satisfying and permanent of his benefactions. Granted that remains, we do not regret that Belloc has dissipated his energy many ways without rearing one monumental work; nor could one wish that he had written an Iliad, provided, he has given that genuine little, vein of poesy in South Country, or that he has written a lofty vindication of the Church, provided had expressed the standpoint of the Faith against the fads and fancies of our time. But Belloc is a treasure-house that has not yet been ransacked to the full; and to those who ask for a towering masterpiece, there may be time yet for such a word. Belloc is still a living force and an active energy. And we may yet speak of this Belloc of ours.

(Blue and White).