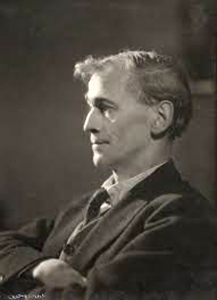

If you ever had occasion to hunt for some of the books of Robert Lynd or any by Sylvia Lynd in one of those wonderful small second-hand bookshops in London where a proprietor resembling the mixture of a presiding deity and an animated Publishers’ Catalogue rules all, the Olympian bibliopole would tell you: ‘Why, yes, of course, they are both together and in the same place.’ And indeed the two names lend themselves to a very apt alphabetical arrangement. But the link is of a. deeper nature than the Olympian’s catalogue. For if you made a few turns from the roaring highways of London and cut northward up Hampstead way, you would light upon a region of repose, where the grove really presents trees and the gardens really contain vegetation. The house is in Keats Grove and a few doors from the house of Keats which is national property and a museum of the poet’s relics. There you will find them, not in crown octavo, cloth-bound with gilt edges, but in the human guise, and both together and in the same place.

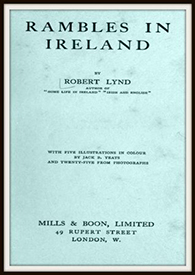

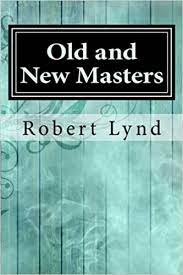

You will find at once that in that house there is no question of choosing a better part, but that both have chosen the same part, and that, within the limits of their excellent choice, there are no feats of derring-do that they are not capable of. Let alone the same part, the^ may even choose the same theme; and Robert Lynd could turn out a charming essay on it while Sylvia Lynd was making her lovely poem. Such a proceeding would have a delightful reciprocity, and it is a pity that Mrs. Lynd did not write a song of the Goldfish when Robert wrote his essay, or that Robert did not write an essay on Goldfinches when Sylvia wrote her poem. Anyhow, to make a division of labour, would you like an essay, full of merry wisdom and laughter and easy, non-technical philosophy? Or would you like some revelation of the hearts and hearths of an island called Ireland? Or else, would you like to learn The Art of Letters and all about Books and Authors, or fathom the Old and New Masters? Robert Lynd would see to it. Or again, would you like a shrewd, penetrating, but genial and tolerant criticism of anything in the world, from Chesterton to the Charleston or from metaphysics to mud? That also would be for Robert. But did you like a gentle poem, full of the still small voice and a-flutter with the sheer joy of life, like the nimble feet of deer or the dance of squirrels munching nuts; or did you like a laugh-story with a dash of fantasy End mischief, a sort of night-cap before being kissed by Mother in to bed, or a Children’s Omnibus full of the best things of the world for your children and everybody else’s—all that is the cue for Sylvia Lynd. But were you too greedy and wanted all at once even that would not ruffle these dear givers a bit. They will only retire a short while apart, each to the Muse’s corner, and quickly produce you the things.

It is indeed in this very obliging spirit, that is, for the delectation of us, the asker? (and our name is Legion, for we are many), that Robert Lynd has penned off those weekly masterpieces on the ordinary things that lie at the roots of an ordinary man’s heart, like a sixpenny lunch, or the two bob on the Winner, or on being rather idle, and that the collections of these gay deliverances in composite bunches have been given a local habitation and a name under pretty titles, such as The Blue Lion, The Orange Tree, The Peal of the Bells, The Little Angel, and so on. And the happy sequence, let it be said at once, goes on in undiminished vigour. For only a short time ago when The Goldfish and later It’s a Fine World appeared, a sixth volume and then a seventh had certainly not withered, nor custom stated that infinite charm of a familiar, friendly style. Rather, its loveliness increases; and where less fortunate persons would gladly give their nights and days to such a style, the stylist himself devotes to it something like half an hour amid the whirring of a newspaper press. Rain, Rain go to Spain; I Tremble to Think; In Defence of Pink—-these also were born amid the thunder of the linotype machines which daily produce that newspaper which Charles Dickens long ago founded. In time the story will pass into legend. Here we need only say that however careless the rapture, the effect is not uncertain. For in all that tub of goldfish nothing glisters, but all is gold; and in all that volume which hailed the world as a fine world a fine point about it slurred over is that it owns a fine Robert Lynd.

But yet, if one thought that there were a grand Arcanum of that process, some secret received of the wise masters of an earlier day which Robert Lynd kept up his sleeve when he wrote, and one would certainly be wrong. One may hug the delusion that here it was the manner of Joseph Addison which the contemporary essayist was remembering; or that there it was a distinct reminiscence of the known legerdemain of Oliver Goldsmith; for really no man has perhaps ever expressed himself in the friendly and intimate style of these two older hands all his time until Robert Lynd wrote. One wonders and asks. One is then told that the answer is in the negative; whereat one feels very strongly that Robert Lynd, who has succeeded so brilliantly in extracting the essence of the essayists for the benefit of readers of a prominent literary paper, should extract for all interested the essence of himself too, and thus out with the truth.

Meanwhile, as there still remains one more volume to be considered entitled The Green Man, a fairly reliable clue may, for all you know”, lurk there. You proceed to it warily. You firmly refuse to be trapped in the pitfall laid by the author to induce the belief that a green man is a capable journalist who is just learning to handle a motor wheel or to swear in the company of a caddie. You have a feeling that the green man is rather better interpreted in terms of spirit; and as Robert Lynd so significantly likes to christen his books with the names of public houses, you at once remember that the last name too is traceable to the same Christian godfather-hood and that it may be seen for a threepenny ‘bus ride from the City. Wherefore, you advance the very penetrating thesis (and it is probably correct this time) that the essence of the writer’s essay-craft is a convenient public house, which is, in fact a much better way of saying that Robert Lynd’s essays are in tune with the noble inward enjoyment of the popular goods of Christian democracy; hence their beauty. And if you were not yourself in harmony with that tune, or, better, if you were never in the holy habit of asking ‘What’s yours ?’ or of saying when, you may qualify as a good Tolstoyan or a devout Shavian, but you will scarcely be worthy of communing with Robert Lynd.

It is, of course, no easy matter to expound the concepts of learned clerks on abstract things; but one has a feeling that it is no easier matter, either, to explore the unlimited sense and sensibilities in the commonest concrete things. Who would unravel the gigantic potentialities of a penny? And human nature’s harassing dilemma over pennies in a toy post-office deposit-box? Are not all the wise saws about pennies and all the modern instances of money-boxes the huge result of the very unsporting human desire for a penny as a thing to keep in a box? And do not all the little graceful expenditures and fine gestures we make unto ourselves depend upon the beautiful impulse to treat the penny as a thing to take out of a box? Would there not be a transcendental Ethic of the money-box? There is; and Robert Lynd states it that ‘the only kind of money-box consonant with virtue is a box from which you can take the money out when you want it.’

But, indeed, it would be near an insult to suppose that all these are rhetorical questions of Robert Lynd. Far from it but when you have perused his wisdom on the money-box, or any other thing, you may even embark on further (and of course, very insipid) cogitations pf your own. But you have acquired from this sagacious and best philosopher of This and That the sensational and sublime truth that a penny or a money-box, like the one million other common everyday things that he discusses, is a thing to think about. Thoughtless millionaires have made their penny and kept their wicked money-boxes; but very rarely has a penny made new thought and a money-box made a new book. And with an original philosophy Robert Lynd starts a whole book, The Money-Box, and proceeds to describe the thrills of any little Mary Ann who, in the spirit of the new ethic, fills (or empties) the box. But, for one thing, and beyond the money-box, Robert Lynd is one of those writers who can describe anything and whose descriptions actually and faithfully describe. Of the Cup Final or the Grand National or of Miss Betty Nuthall’s feats Robert Lynd could write a sheer picture where the thing happens, not through a glass darkly# but before your very eyes. All the hectic events of the sporting life pass away; and all our punting of yesterday is one with Nineveh and Tyre. But were you a lucky dog and had your day when Captain Cuttle won the Derby and Varzy took the Royal Hunt Cup, and like to live the thrill of these again, or did you merely want to see Carpentier V. Cook or the whole humour-laden dramatic business of the Tests of 1921—no cinema would make that dead past live. But Robert Lynd’s Sporting Life would. In your mind’s eye, Horatio!

And as for criticism, Robert Lynd’s critical work really criticizes. That is to say, much of it does try to give, in the time-honoured fashion of the critic, a judgment on work that it examines. Such an examination could not avoid applying the elemental tests of whether the work is good or bad, right or wrong; though this gentle critic would break the truth sometimes gently. At any rate, his criticism does not resort to the usage of terms at once loose and vague and unmeaning which, requiring no discipline of the mind, have made the criticism of to-day defeat its own purpose. He does not fear the appeal to fundamental ideas; nor does Sylvia Lynd, who recently labelled a volume of modernist verse as ‘Verse and—Worse‘ Of Keats, Robert Lynd is the ideal critic, a fact which Everyman’s Library has grasped to advantage; for the Lynds live only two doors away from the house of Keats, and Robert has only to shut his eyes and look back to see Keats’s Nightingale being written under the apple-tree in the garden or his break-fast loaf baking in the household oven. And to add to that, Robert Lynd has all the sympathy and, what is specially the, equipment of a true critic of poetry, a definite theory of poetry, which has been set forth with the finest sagacity and clearness in our time in two remarkable prefaces to Sir Algernon Methuen’s anthologies. In their limpidity and deep understanding these two essays may grasp hands, across the vast abysm of time, with that seminal work of criticism, The Poetics, which, to its author at least, was nothing more than The Uses of Poetry and Poetry and the Modern Man of the age of Alexander the Great. But, as a tangible difference, it must be added that the great writer of the earlier theory of poetry would doubtless have mentioned his wife— if she did happen to write good poetry.

And as for criticism, Robert Lynd’s critical work really criticizes. That is to say, much of it does try to give, in the time-honoured fashion of the critic, a judgment on work that it examines. Such an examination could not avoid applying the elemental tests of whether the work is good or bad, right or wrong; though this gentle critic would break the truth sometimes gently. At any rate, his criticism does not resort to the usage of terms at once loose and vague and unmeaning which, requiring no discipline of the mind, have made the criticism of to-day defeat its own purpose. He does not fear the appeal to fundamental ideas; nor does Sylvia Lynd, who recently labelled a volume of modernist verse as ‘Verse and—Worse‘ Of Keats, Robert Lynd is the ideal critic, a fact which Everyman’s Library has grasped to advantage; for the Lynds live only two doors away from the house of Keats, and Robert has only to shut his eyes and look back to see Keats’s Nightingale being written under the apple-tree in the garden or his break-fast loaf baking in the household oven. And to add to that, Robert Lynd has all the sympathy and, what is specially the, equipment of a true critic of poetry, a definite theory of poetry, which has been set forth with the finest sagacity and clearness in our time in two remarkable prefaces to Sir Algernon Methuen’s anthologies. In their limpidity and deep understanding these two essays may grasp hands, across the vast abysm of time, with that seminal work of criticism, The Poetics, which, to its author at least, was nothing more than The Uses of Poetry and Poetry and the Modern Man of the age of Alexander the Great. But, as a tangible difference, it must be added that the great writer of the earlier theory of poetry would doubtless have mentioned his wife— if she did happen to write good poetry.

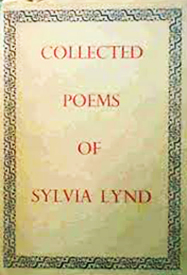

And Mrs. Lynd does, of course, write good poetry. Her poetry is so uniformly good that it cannot be produced in large quantities, but as the divine efflatus of an inspired moment, the fruit of a rapturous spiritual experience. These are rare things in life, and Mrs. Lynd has crept to Parnassus heights with what is quantitatively the smallest poetic bundle under her arm. But, qualitatively, it is another story, for all the charms of all the Muses oft could deck one lonely word, all the colours of the rainbow merge and sparkle in a phrase, all the poignancies of the heart speak their full tale in a stanza. If it may be believed that the test of the mind poetic is a capacity to see a world in a grain of sand and a heaven in a wild flower, why, Sylvia Lynd could see any number of such visions in those objects; and would it greatly matter if her sand and her wild flower were only a walking distance away on the Heath, seeing that as a type of the wise she could be nothing if not true to the kindred points of heaven and Hampstead? One could always assure her that her wings are most delightful things; but it is at the latter address that she always takes off, to soar towards the other. And after the straightest and the swiftest flight she does come back home too. For no maker of poetry in our time has expressed such a haunting sense of home, and the delicate pathos of those many-splendoured things at home that are the children there. Perhaps no mother has sung her children better. Perhaps no mother in our time has expressed what all mothers feel in such a refrain as:

And Mrs. Lynd does, of course, write good poetry. Her poetry is so uniformly good that it cannot be produced in large quantities, but as the divine efflatus of an inspired moment, the fruit of a rapturous spiritual experience. These are rare things in life, and Mrs. Lynd has crept to Parnassus heights with what is quantitatively the smallest poetic bundle under her arm. But, qualitatively, it is another story, for all the charms of all the Muses oft could deck one lonely word, all the colours of the rainbow merge and sparkle in a phrase, all the poignancies of the heart speak their full tale in a stanza. If it may be believed that the test of the mind poetic is a capacity to see a world in a grain of sand and a heaven in a wild flower, why, Sylvia Lynd could see any number of such visions in those objects; and would it greatly matter if her sand and her wild flower were only a walking distance away on the Heath, seeing that as a type of the wise she could be nothing if not true to the kindred points of heaven and Hampstead? One could always assure her that her wings are most delightful things; but it is at the latter address that she always takes off, to soar towards the other. And after the straightest and the swiftest flight she does come back home too. For no maker of poetry in our time has expressed such a haunting sense of home, and the delicate pathos of those many-splendoured things at home that are the children there. Perhaps no mother has sung her children better. Perhaps no mother in our time has expressed what all mothers feel in such a refrain as:

These will not fade me, they are made,

Of a delight that cannot fade

So long as loving eyes may look

In Memory’s well-painted book…

And when they tend flowers within the garden gate, the flowers become flocks, and the little gardeners ‘shepherds of the flocks’; but the pleasant office develops at the, end into the vision of a future day, a distant sign and a symbol of a higher sort of shepherds:

Shepherding through this world of ours,

Truth, Justice, Laughter, and—the Flowers.

Then Sheila may play Haydn. When Sheila plays Haydn, her mother, who is a poet with an exquisite sense of simile, visualizes the deer going to the brook to drink—in fact, she says, a thousand pictures, of which she gives only one more, a superb index to all the rest so regretfully passed over in silence:

And at thy sound I go remembering,

About the woods of every vanished Spring.

And there is the Small Daughter, a delicately poignant piece with wide exacting eyes (beautiful exacting eyes). It would appear to begin with a moral and ends with a maxim, or the other way about; but the whole really is neither moral nor maxim, but a delicious reflection of Mother. Sunt lacrimae rerum: which is to say that there is an element of Mother in every one which is ever on the brink of gathering in, in treacherous fashion, at some of the sad music of humanity. This Sylvia Lynd knows.

The Lynds, like Mr. Ambrose Tillotson in one of Sylvia’s stories, ‘love man and bird and beast.’ It would appear that among themselves they love and never quarrel, because by a beautiful policy of give-and-take they simple give each other dedications; and where a little while ago we observed that the prince of philosophers would have readily illustrated his poetic theory with samples of his wife’s muse, one may here at once turn the tables on the Stagirite with a question as to how many books he dedicated to his wife (if any), or how many she dedicated to him— for instance, with such an ecstatic ejaculation as ‘To You, my dear Aristotle’. To the rest of men, the Lynds with great kindness of heart give tea and cakes and the best gingerbread in the world. An excellent inmate of their house of the canine kind called Peter having recently signalized his deftness with an (electric) hare, almost became a thing for verse, a dicendum musis, which is a triumph for a beast. But as for birds, all Mrs. Lynd’s books of verse, or even all her prose writings are ‘stories for ornithologists’ and, at that, stories with- a terrible moral for scampish boys and diabolical gentlemen with pop-guns. And titles like The Goldfinches, The Swallow Dive, The Thrush and the Jay could add any day a zest to any kind of zoological inquiry, even to make a bright page in Aristotle’s ancient work on the Natural History of Animals. For perhaps very few human beings have such an eye for these mysteries as this poetess laureate of the R.S.P.C.A.: ‘the jay’s sky-blue feathers, the fiery crown of the thimble-sized gold-crest, and the primrose wings of the siskin.’ And when the goldfinches returned she has not harboured them; far from it, it is the goldfinches have given Robert and herself umbrage, and she pleads with the birds to be allowed to share with them the green garden, for ‘we cannot all be goldfinches, in such a world as this.’

And if to birds are added flowers and colours and Nature and books and happy Robin-Goodfellowishness and joie de vivre, you have there all the more important things necessary to one who is yet a vivacious girl at heart, to make a right royal celebration of life. Flowers and colours are in effect the same thing, and it is not for nothing that Mrs. Lynd’s last volume of verse bears the title of The Yellow Placard. And if Mrs. Lynd had not selected letters she might have easily been the best executrix of colour schemes anywhere, for wherever there is brightness and beauty and liveliness she is at her best, and that because life to her is a supremely bright, beautiful, and lively affair. But even this life world not be a congenial thing if there were not a bit of mischief or leg-pulling and banter too. So in her stories she uses the medicine in some such way as follows:

‘Mr. Muffin and Mr. Mouse, each wore his hat slightly crooked, pressed down over the left eyebrow. This was to indicate that there was nothing in civilized life that they did not know.’

Or,

I picture the boys and girls, on the long sofas and Persian rugs, intent for a few brief mornings upon belts of straw and ivy buds, busy with coloured paper, reels of wire, scissors, laurel boughs, everybody in high spirits,-eyes bright, lips carmine, the atmosphere of chaff, and flirtatiousness that is called for other reasons Pastoral Plays.’

Or,

‘It was a journalist’s silk hat: that is to say, it was the first silk hat he had ever had, and the only one he was ever going to have. It lived in a band-box beneath his bed. Its appearance was the hoisting of the Storm Cone. He wore it when he attended Royal functions or stood bail for a man. Lacking it, Fraser believed that no journalist is offered an editorial post. He attributed such successes as he had entirely to its influence. A silk hat is a sign that a man is an able man, a punctual man, a man with a sense of responsibility. You can only roll once in a silk hat,’

Wherefore it would be quite understandable if any publisher of Robert or Sylvia Lynd advertised their work as ‘tonics for tired Tom.’ For if Tom is run down, these books are good refreshment and recreation. And when all our sport has become stale, and one thing after another in the series of those admirable reprobate flippancies has been exhausted, there may be a new diversion if an intrepid editor one fine day asked Robert Lynd (who had forgotten his wife among the contemporary poets) to review Sylvia’s and in turn requested Sylvia Lynd (who mischievously thinks that classics in English have ceased to be made) to criticize the latest of Robert’s classic essay-craft. When even that is past, there may be a yet further distraction for those who can summon up courage, which is, to establish a sort of medieval quodlibetic disputation, from the standpoint of an impartial reader like the Man-in-the-Moon, whether Sylvia is a more imaginative writer than Robert, or Robert a more graceful stylist than Sylvia. , An historical-minded gentleman may throw in a query whether this right and singular question has ever heretofore been discussed in any debating society whatsoever, Westminster downwards. And a carping critic may add: if not, why not?.