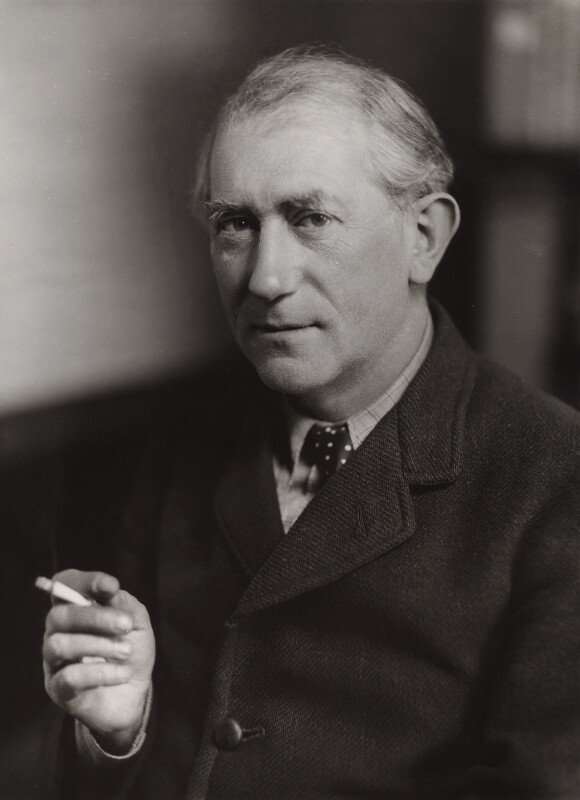

An Intimate Glimpse of Sir John Squire, in important activities other than those of famous critic, poet or writer who can put his hand to anything.

When I first met J. C. Squire (Jack with his familiars, John with his brothers and sisters and Sir John with all Europe, for it would have caused a sad deficiency in any decent turn of adventure not to have met Squire) and within a minute of having done so he asked me to a lunch with him. He wrote at once the date of this lunch with him on a desk calendar before him. Then he wrote the date of this same lunch again on a piece of paper before him and this he handed to me.

Squire is that sort of fellow, a perfect luncher-with, every detail ensured, one who would never fail you. One gets to know later that is on this fundamental quality of dependability that the whole of the regime of his Squirearchy, that is to say, his huge personal grip on England turns. No one knows better than Squire does where the food is good and the chef is an admirable hand and the drink good too and the proprietor is a sportsman and the waiters do good to your soul as you help yourself to the things they serve you with. The company in such a place would all know Squire and the only difference would be that while some would be calling for Squire, others would be halloing Jack and yet others pointedly enough hailing the old boy.

I should not like to imply that Squire himself is taciturn and would not be calling for people or halloing or hailing other old boys. He does. Of course, it would not be that Squire would emulate his namesake of the elder order (teste Mr. Joseph Addison) and severely ask the wife of one John Matthews how the said John Matthews was getting on (meaning a rebuke for the said John Matthews for not being there), nor would he, I think, ask with similar intent the other boys how their wives were getting on. So good a luncher-with as Squire knows that wives are no good on these occasions. But I could rather vouch for Squire leaning across and, in a rather audible voice which in the heathenish atmosphere of boiled shirts and diamond studs would have been scowled upon, but among Christian men does great good to the soul, asking from a farther away table who would begin a recital about a great old game. At the end of which Squire would know that another little drink would do no harm at his table.

All proprietors of good restaurants know Squire and with great readiness come within the regime, because the Squrearchical patronage is a synonym for good service; those who don’t are all keepers of bad ones and therefore to be under a ban, and their food, if you have tried it, will be invariably bad, the drink foul, the manager (the proprietor is always absent in the bad ones) a cheat and the company, swells or swine. Even in Heaven I think the patronage of Squire will be a great thing for restaurant-keepers. His advent there would set a celestial lunch-habit in motion. Within a minute of meeting Peter at the Gate he would have given the eternal Janitor a date, for lunch, writing it down in his own memorandum-book and inscribing it again for Peter’s remembrance.

Squire kept an office (in those days) comprising several little rooms reached by a creaking little narrow stair-case, but what business he transacted there I was not at pains to enquire. That was his business. The address was opposite Temple Bar, over against the very spot at which the King riding in state into the City is ceremonially empowered to do so by my Lord Mayor by the handing over to His Majesty: of the City’s sword. At that spot also the Strand ends and Fleet Street begins. I do not know if I should attach any significance to the question of the location of Squire’s place of business. Was it some ancient prerogative devolving on him from the older Squirearchy that he should take up his stand at the place where the older and even rascally squires’ hold on the country ended and they themselves had to shake off their rusticity to enter the city? Or was there any special meaning in Squire’s offices standing at the entrance into Fleet Street like the Pillars of Hercules into the Mediterranean?

I never ventured to ask. But on my first adventure into these offices I was’ bound to recognise with delight that Squire’s neighbour was the keeper of a small shop dealing in little trinkets and curios which prided in the name of ‘The Ceylon Shop.’ Squire, maybe, had some interest in this shop, or maybe, not; but he appeared to know Ceylon and to be even capable of setting right a misquotation I made of a line by the poet, Mr. John Masefield, about’ a tea-planter’s lodge in the plains in Ceylon’. This incident is explained by the conjecture that Squire sometimes read a little poetry for whiling away a spare moment. Squire’s own offices bore a signboard on the outside bearing the image and superscription of the old Roman god Mercury. Why does he favour the old Roman god Mercury? But, then, why does anyone else favour anything else? ‘At the sign of the Mercury’ may have been, I fancy, the last of those ancient hostelries of London where men drew wine from the wood and drank ale that really traced to hops and beer that really derived from barley.

Anyhow, when Squire took his stand under his sign and whistled for his taxi-cab, the effect was electrical, or rather squirearchical. All taxi-cabs that ‘hold the freedom of the Strand and Fleet Street knew Squire.’ An empty cab flying past Temple Bar would take immediate notice of the whistling Squire, have brakes clapped to, veer round devilishly, and in the twinkling of an eye halt at the kerb. All taxi-cabs know Squire for a decent, dependable fare who will not cut the tip too fine. Indeed there will be great to-do to be first in the heavenly taxi-rank when on that great dawn of all Squire going out to lunch takes Peter.

Squire dresses generally in grey flannels and a sports coat and makes not much use of a hat and has the appearance and is, in spite of his being so dismally committed to an office by reason of his business, a thorough open-air-loving fellow. Temperamentally and by choice. All open air matters therefore come within his regime. He knows all that’s worth knowing about the kind of game proper to rugger three-quarters and all about the virtues of decent polo or hockey playership. He is an assiduous cricketer and leads a team of his own called ‘The Invalids’ who play a full fixture card the season through all over the country each year and cap the record by turning out for a match, now famous in real cricket annals, played on New Year’s. Day, This match, of which the success is rated to increase in proportion only to the quality and quantity of snow and the degree of cold and frost and other concomitants of winter attending it, is played by the dauntless ‘Invalids’ as a warm demonstration and a protest against the encroachments of football on the summer.

No greater service has been rendered to cricket than this. And Squire’s ‘Invalids’ being all devoted to Hambleden know better than to think that real cricket is the weak lemon-squash stuff that the M. C. C. and the Country Championship are nowadays making such a bother about. The ‘Invalids’ cricket is made of sterner stuff; their game is of the Homeric epic order which still distinguishes the village-green and out of which the baser game itself was born. When an ‘Invalid’ hitter successfully lifts a ball it generally falls into the middle of a match in the next village green. An incapacitated ‘Invalid’ wicket-keeper has not seldom been known to have been forthwith brought back to normal usefulness with brandy run up from the pavilion (which on less spectacular occasions styles itself the public house.) Oftentimes beer has been known to have invigorated heroes at the very crease, sometimes even the umpires themselves without any detriment to the judgment and wisdom of their decisions. And occasions have not been rare when the final arbitrament of a game has been withdrawn from the green sward and concluded to everybody’s satisfaction in the pavilion. Squire is a great captain: hosper Odysseus—as Homer said. The cricket match described in A. G. MacDonnell’s England, their England is a game played by Squire’s ‘Invalids’.

Squire preserves one or two loyalties towards educational institutions. He has had some connection with Blundell’s and also another with St. John’s, Cambridge, as you will see from the ornamental ties he sometimes wears. He is fond of referring to the school having something to do in Lorna Doone. Squire has read Lorna Doone. It is not clear what other books he might have had time to read at St. John’s but his name appears among the Masters of Arts of that college. This, of course, is not important unless one were sure (and I am not) that he had it in that singularly more exacting Cambridge way of achieving it, by aegrotation; for the rest either towed in the Bump races or ran along the tow-path yelling for all his worth. This excellent qualification explains Squire’s later indispensability to the B. B. C. on the occasion of the Boat Race for a running commentary on the race while being run.

Squire, even otherwise, is a very popular broadcast star. Time and again ladies have written to the Company asking for repeat-items by Squire, just as other ladies have gone all the way to attend speeches given by Squire. Squire is an excellent after-dinner speaker. He is an excellent speaker of any kind. He has lectured to all kinds of people on all sorts of things. He once even stood for Parliament but the electorate was an ass, and remains. His impromptu epigrams are famous. It was in speeches that he seems to have made that now famous addition to Pope’s couplet on Newton and to have evolved the celebrated battle-cry of ‘God for Harms-worth, England and Lloyd George.’ Squire is an excellent chairman, one of the few who can be trusted to have an open bout with the speaker of the evening. He serves with indefatigable zest on dozens of committees and councils and advisory boards and officiates as the patron or vice-patron or president or vice -president or honorary this or that of umpteen associations, societies, .unions and leagues. He: is unequalled as a delegate or representative or even ambassador.

He is known to have crossed the Atlantic on one such ambassadorial function, to have duly carried out immediately on landing his ambassadorial function in New York and to have straightway crossed the Atlantic back again to his business. Which reminds me that Squire has an enormous knowledge of architecture and to hear him on that topic would be to convince yourself, and perhaps rightly, that it is the architect’s business the Squire carries on ‘At the sign of the Mercury’, I remember him telling me that Catholics ought to subscribe towards the purchase of bombs and towards the acquisition of the right of using them on the hideous piles of flatdom contrived in the worst Victorian manner which hedge in Westminister Cathedral, a piece of advice fraught with ardent enough appreciation of the Neo-Byzantine-Nay more, Squire is an acute judge of even other types of beauty too, and with Miss Tallulah Bank-head has officiated as a judge in a beauty contest among Oxford Undergraduates. The winning candidate was awarded the honour of kissing Miss Bankhead and of shaking hands with Squire.

Squire, as an open-air-loving fellow, is a great patron of open-air theatricals and extends his Squirearchical patronage to all theatricals of the sort organised since that famous producer, Peter Quince. Squire is particularly a patron of a very devoted society of such players who hold shows every year at Petersfield in Surrey on the premises of a large country house. His patronage was very prominent one year when these players enacted the most lamentable comedy of the Coppy Gipser, a play which remains as all good plays should, in script. Squire sat by me in the auditorium and appeared to enjoy every bit as it came of the play and without any anticipation of the enjoyable things, as all spectators do, but at the lusty shouts that arose later for ‘Author’, Squire to my wonderment took this call and delivered himself of a considerable oration without compromising himself on the subject of the authorship. I understood that the gesture was purely Squirearchical, and that having been patron of the show and even taken a hand in selling programmes and being ready enough speaker to spare the nerves of a shy and anaemic author, Squire ably filled the breach. Squire is a wonderful brick at filling any kind of breach. It is no doubt in recognition of this that some 500 people suddenly resolved some years ago to offer him a dinner and a short while after the King raised Squire to the Knightage.

To round off the day. Squire is an inimitably companionable diner, one who can pull through the common afflictions of official dining by always improvising some scheme of private exhilaration. I remember his companioning me at one such dinner held in the City in the ancient hall of a Worshipful Company. Squire came with a particularly large rose in his buttonhole. Not that Squire is a poet and from Bloomsbury indites a periodical dithyramb on a daisy or occasional sonnets to a bed of sweet lavender, but Squire is an excellent amateur gardener and knows how to grow and cull his own rose. He knew that the orchestra were playing Brahms even without consultation of the musical programme. Squire knew Brahms. One of the afflictions of the evening was the rodomontade of a Conservative Cabinet Minister who was down for the speech of the dinner. But before this event was reached Squire had already forecast with fine accuracy the whole of the impending speech, which rendered two diners at least free to do something else.

This took the form of a respectful study of the grave, dignified and beautiful physiognomies of the waiters as contrasted with the paltry, commonplace, and unprepossessing physiognomies of the diners. There was a dignified, calm, reflective face of Newman waiting on the ordinary, bland, office-boy-like face of the Cabinet Minister. In the intervallums of liqueur rising and leaving a portly and elderly fellow-diner fell in with us and after some talk enquired of Squire if he were a chemist. This man was apparently one of those very poor devils who had never heard of Squirearchy. Squire seemed inclined to demur and resent the unconscious affront to his architect’s business. But after all, all that preoccupation with the subtle and profound business of human emotion and psychology, which is Squirearchy, does savour, if you know what I mean, of the analytical and precise methods used by dependable chemists. I should, therefore, heartily add that Squire may be a top-hole chemist.

A clean hearth, a good fire and the rigour of the game’ said Mrs. Sarah Battle (now with God). The serious purpose of life served, the lady afterwards unbent her mind on a book. It may be that Squire himself after a hectic and crowded round of Squirearchy does unbend his mind every day also on a book. There is that interesting little yarn going round that he has done a thing or two in that direction also and written some creditable prose and even some tolerable verse. But against the larger, more comprehensive and more elemental aspects of the business of Squirearchy, against the timely dictatorship of this adorable Mussolini who has brought back the Classical unities to fundamental human functions like eating, drinking, playing and good fellowship and has therein, though even truculently, restated values and banished the critiques of impure reason, this matter of his recreational scribble (if so he does) is a detail too trivial to dilate upon.

Let it pass.