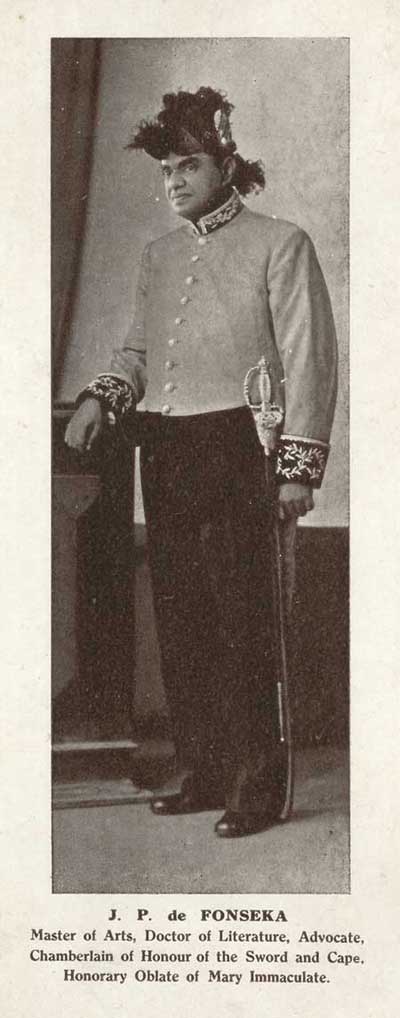

Dr. J. P. de Fonseka, the new Chamberlain of his Holiness the Pope, has imprinted himself on the Catholic consciousness of Ceylon as the supreme example in this generation of an incomparably great defender of the Faith. He has used his prodigious talent for writing in a manner and with a prodigality which should be regarded as an inspiration to all those who have hitherto watched through young and troubled eyes the conflict of ideas and ideologies in the contemporary scene. J. P. de Fonseka’s ideas have derived their consistency, their freedom and mobility, and their gracious temper from the perennial Catholic philosophy which deeply informs all his writings.

Dr. J. P. de Fonseka, the new Chamberlain of his Holiness the Pope, has imprinted himself on the Catholic consciousness of Ceylon as the supreme example in this generation of an incomparably great defender of the Faith. He has used his prodigious talent for writing in a manner and with a prodigality which should be regarded as an inspiration to all those who have hitherto watched through young and troubled eyes the conflict of ideas and ideologies in the contemporary scene. J. P. de Fonseka’s ideas have derived their consistency, their freedom and mobility, and their gracious temper from the perennial Catholic philosophy which deeply informs all his writings.

There, is a sense of pervasive fullness in his treatment of the varying themes in which he engages his un-resting pen. Whether it is on a secular theme, or the exposition of some religious idea, he never fails to leave the impression of writing from a full and capacious mind, sure in principles, abundant in vocabulary, joyously novel in his method of approach and discriminating in substance. He jests with the urbanity of a humane philosopher on all things under the sun, and laughingly and debonairly drives a swift sword-point into the heart of some modern error which mincingly parades as modern truth. He has done the Catholic community in Ceylon, and even outside our boundaries, a very great and lasting service by his exposition of essential truth in its manifold manifestations. His most significant contribution recently has been his light yet searching analyses of the gospels and his luminous exposition of the whole pageantry and purpose of Catholic ritual. Thousands of his co-religionists are very grateful to him for his ministry of information in these subjects.

There has been a rich amalgam of influences in the making of the mind of J. P. de Fonseka. It is evident that men learn quicker from contacts with some towering personality than from books. In this direction, J. P. has been almost excessively fortunate, for no man born in a dull intellectual climate like ours can dream of the large emancipation of being admitted so readily and so responsively into the invigorating intellectual atmosphere of England. But this happened to J. P. de Fonseka at a most impressionable period of his life, and continued long enough permanently to liberalise his mind.

To have met Chesterton must have been like being introduced to a tornado of ideas. J. P. must have been torn out of his imitative insularity and the whole bulk of him carried away on a high lashing tide. When restored to himself, J. P. would have found that he had also grown into a thinking being of larger proportions than if he had merely read Chesterton in our backwaters.

The height, breadth and depth of Chesterton’s mind is not sufficiently recognised because of his elemental passion for fun in the bulk of his journalistic essays. But it must not be forgotten that Chesterton wrote “Orthodoxy,” “The Everlasting Man” and a study of St. Thomas which last, scholars who devoted a lifetime of concentrated examination into the writing of the Angelic Doctor declared hg<d probed much deeper into the mind of the greatest philosopher of all times than they themselves had done.

When we read J. P. we must not forget that this association with Chesterton has fundamentally enriched the personality of the happy disciple and that to the extent to which J. P. resembled Chesterton, Chesterton also resembled J. P. de Fonseka so that those who have missed contact with the master can find a good part of him in contact with the disciple.

This certainly is not a case of the survival of the fittest, but a survival of the spirit and temper of a great personality, authentically recognisable and vicariously vital, yet abating nothing of J. P’s own originality, but rather stimulating it along its own independently elective lines of development, and creating one of the strangest but most productive literary phenomena of our day.

This certainly is not a case of the survival of the fittest, but a survival of the spirit and temper of a great personality, authentically recognisable and vicariously vital, yet abating nothing of J. P’s own originality, but rather stimulating it along its own independently elective lines of development, and creating one of the strangest but most productive literary phenomena of our day.

J. P.’s other contacts have an interest in a less determining degree of but collectively their influence cannot be ignored. Bernard Shaw, the Grand Old Man of English letters, counts J. P. de Fonseka among his personal friends. I had long ago a newspaper cutting which I have long since lost sight of in which a journalist wishing to preserve for posterity an actual recording of a conversation between Shaw and Chesterton ensconced himself behind a large chair and took down in shorthand a very stimulating war of words.

J. P. must have found it a very large experience to be privileged to the intimacy of such combats of the giants. Then there was Wilfred Meyhell, with his mind redolent of the memories of Alice Meyhell and Francis Thompson both poets rich in skyey grain, Walter de la Mare, the high-priest of modern wizardry in words and strange phantasy, A. P. Herbert torrentous of light verse, Sir John Squire and others whose companionship constitutes treasury of stored remembrances and a possession for life, more precious than rubies.

We cannot fail to realise that J. P. is a potent force in the world of letters, not only here but outside. He is read in America and England, and the Doctorate of Literature conferred upon him by the University of Ottawa is a sign of his growing fame. J. P. owes it to the world of English letters that he should no longer delay in giving us the study of Chesterton for which our curiosity has been on edge these many years. It is .a tribute to a memorable friendship which must be sooner or later paid, and paid generously on a scale which will justify the application to it of the fit word monumental.

J. P. is in the maturity of his powers. His style has acquired an ease and flexibility and suppleness which is equal to a great task in literature. The anxious public should not have long to wait. By this means J. P. will link his name indissolubly and deservedly with Chesterton and build a monument to friendship more lasting than bronze.

Quintus Delilkhan

Aquinas (1947)