Fatness is a paradox and fat men are paradoxes. In the midst of slow, moderate growth, there rises up an incessant and surprisingly fast ‘vegetation’ which seems to increase even as you look on. In the midst of ordinary-sized mortals, there appears a strange creature of stupendous proportions, of incalculable weight, a vast mass which can safely harbour any three distressed fellowmen under its gigantic frame. ‘Inconsistant Nature,’ one is forced to say. ‘Why should she introduce into the company of Lilliputians, a band of Brobdingnagmen, into the assembly of dwarfs, a towering colossus? Why? I cannot say, but the matter still remains a fact that there have been, are and will be such awe-inspiring creatures whom people call fat men. And today they are as numerous as ever; in every twentieth house in our city you could find unmistakable traces of a fat man’s presence. His giant frame, his hill of flesh, his gross mountain-form towers high above everything else in the house; all men there yield to his size; all men have to bow to the dignified majesty of his fatness. The reign of fatness has begun.

Fatness is a paradox and fat men are paradoxes. In the midst of slow, moderate growth, there rises up an incessant and surprisingly fast ‘vegetation’ which seems to increase even as you look on. In the midst of ordinary-sized mortals, there appears a strange creature of stupendous proportions, of incalculable weight, a vast mass which can safely harbour any three distressed fellowmen under its gigantic frame. ‘Inconsistant Nature,’ one is forced to say. ‘Why should she introduce into the company of Lilliputians, a band of Brobdingnagmen, into the assembly of dwarfs, a towering colossus? Why? I cannot say, but the matter still remains a fact that there have been, are and will be such awe-inspiring creatures whom people call fat men. And today they are as numerous as ever; in every twentieth house in our city you could find unmistakable traces of a fat man’s presence. His giant frame, his hill of flesh, his gross mountain-form towers high above everything else in the house; all men there yield to his size; all men have to bow to the dignified majesty of his fatness. The reign of fatness has begun.

At home, the fat man is something sacred, something far above the rest of mortality. At every hour of the day, no matter how much other work there may be, the fat man’s interests have to be looked after with the greatest care.’ The morning comes and the preparations are made for his rising, his wash, his morning meal; servants fly here and there and go hoarse, calling for towels and sponges; one fellow helps him to dress, pushes his trousers up his monstrous legs, laces his boots, often and often asking himself how long ago it is since his master has last seen his own knee. After much bustling and hurrying, the great man sails out or rather creeps out of his chamber and rolls along to the laid out table. One waiter deposits the vast mass of humanity on a chair made for the express purpose; another serves the eater, never allowing him to tire himself, and while the eating goes on, both attendants wax thoughtful and wonder how long the operation will take. At last the work is done; one fellow dashes to place the capacious lounging-chair in the sun-shine, another bellows for stuffed-cushions and long pillows and morning papers. The swollen parcel stretches himself and the attendants leave him blessing their stars that at least one thing is done, and slip away lest they meet with further orders. The fat man’s bathing-time is the next moment of stir and noise. The water-pipe looks indignant that it has to pour out three times as much water for this fellow than for any other; the tub has to be filled to the brim and buckets of water have to be poured by the hand of a wretched soul to the head of the gorbellied mammoth who sits on a stool, gasping and groaning and panting. Another time of positive agony is the fat man’s afternoon sleep. The featherbed, countless pillows long and short, flannel coverlets are prepared for their torture; the torturer comes along and locates himself on them. The iron creaks mournfully, the mattress sinks in with the weight, the pillows are jammed to death. And in the twinkling of an eye you hear noises as of a distant thunder, as of a roaring lion, as of a snorting horse. But the noise comes from the innocence of fatness. It is the fat man sleeping. And when he sleeps the pass-word is ‘1ft no dog bark’. A pin falling would disturb him and the house-inmates talk in the dumb language of signs and gestures; they dare not whisper for fear the sleeper would wake up before the usual time.

If the fat man’s lot is the happiest where the life in a home is concerned, his lot abroad, out of doors, is the gloomiest. Ask any fat man whether this is not so and he will recount to you how many sad moments, how many woeful adventures he has come across, how many tears he has shed, how many times cursed the hour of his birth. He is not born for travel, nor is travel a thing for him. He need not set out on distant voyages to far off lands, he need not journey for days on end; let him simply step over his threshold for his unusual evening stroll, and see the effects of it.

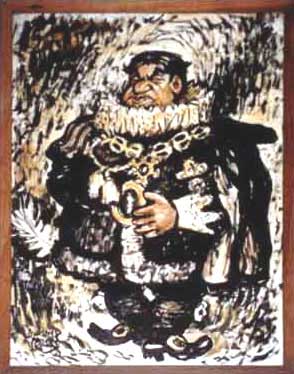

A monstrous specimen of humanity, a tun-bellied, big-headed, large-faced fellow with a height just a little more than his breadth, he steps out clad in as much flannel as would clothe a dozen little urchins; he works his mighty way. A spell is east on the scene; men’s eyes fall or laugh, maidens titter in the houses and by-standers cast their remarks: ‘Heavens! look at him’ one is heard to say; another,’ mercy on us, what is this?’ a third.’ see the Berkshire, see tallow see butter; and yet another vociferously remarks how inadvisable it would be for all men to buy > their food stuffs from the fat man’s provision dealer. Each of these ejaculations the fat man is forced to hear and each is a sword in his heart, yet he pretends to be unaffected and proceeds. Mothers silence crying babies by showing him as their devourer; fathers introduce him to mischievous sons as a wonderful wizard who steals children away and uses them as slaves. And little schoolboys at his back try to imitate him with protruded stomach and laboured step and call him alternately ‘plumpy goose, boar-pig, mammoth, sweet beef’ and so on. Tailors’ and shoemakers’ mouths water at the thought of the bargain of suits and shoes for him, and undertakers sincerely wish his death, while inn-keepers go mad to think of his taking a meal and paying ordinary fare. And rickshaw-coolies look another way, fearing he would call them for work; the very horses of gigs on hire look imploringly at their drivers and wish they would avoid all men of such magnitude. Now certain college youths, meet him face to face and, poor mortals, they laugh in their pocket-handkerchiefs and, versed in Shakespeare, pass remarks in Shakesperean, words. He, ‘fat-guts, wool-sack, Spanish pouch’ says one; ‘greasy tallow-catch, horse-back-breaker, bed-presser’, another; stuffed cloak bag of guts… out of all reasonable compass, oh! the embossed rascal’ a third, and so on, wasting the nomenclature set apart for Sir John Falstaff on this great fat man. Remarks and laughter were created for him they are his cross and he must bear it up patiently. If he were only of the turn of mind of the tun-of-man knight of Boar’s Head he could proudly say: ‘Men of all sorts take a pride to gird at me; the brain of this foolish-compounded clay, man, is not able to invent anything that tends to laughter more than is invented on me. I am . . .the cause of wit in other men.’

(Blue and White 1916).