LANKA (for of Ceylon’s many names that name has been the dearest to her poets and her people) has ever been the seat of kings. Even in the faintest mists of antiquity was she linked with a king: in the Ramayana, perhaps the oldest poem of the world, the theme is a war waged by Rama, King of India, on Ravana, King of Lanka. But the prime fact of her history was a crossing over from India to Lanka by Prince Vijaya, about 550 B.C. The crisis of that adventure was that the adventurer never returned. He was of the Sun Race of the Aryans, who said that the sun was ‘the first of their race’; and his people, likewise descended, also called themselves Sinhalese (the People of the Lion Race), and ever after depicted that lordly beast rampant on their standard.

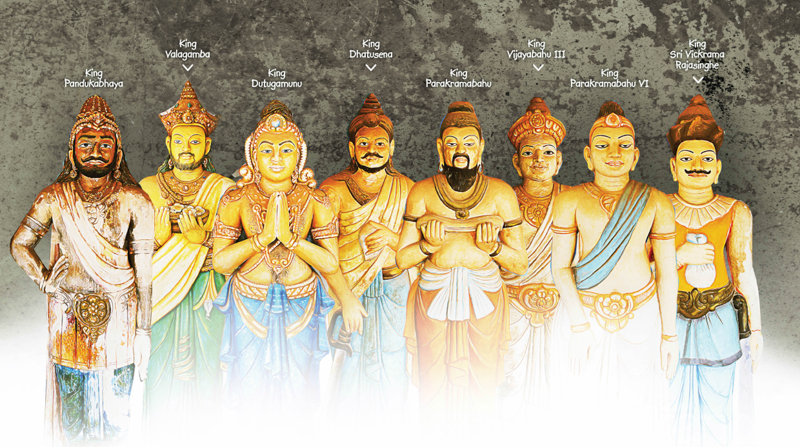

To the succession from Vijaya for nine hundred years posterity has accorded a greater name: it is the name of the Maha-wamsa, or the Great Dynasty of the Kings of Lanka. Thence onward the Suluwamsa or the Lesser Dynasty, which came to an end in 1815 with Sri Wickrama Raja Singha, the last King of the Sinhalese:

‘And after they had banished the King who was a scourge to the country, the English took possession of the country. This was the end of the Sinhalese independence which had endured for over two thousand three hundred years.’

But it could be said that the monarchy did not end but was only replaced, for, as a contemporary writes:

‘When on the 2nd March, 1815, the treaty had been read to the chiefs and the people assembled, the British flag was hoisted, and a royal salute from the cannon of the city announced His Majesty King George III sovereign of the whole island of Ceylon’.

Lanka passed under the Crown as the first of its colonies. But for fifty years before that the British had been in Ceylon. Before them the Dutch had held the Maritime Provinces in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: their bequest to Zeilan was their system of law. And before the Dutch, the Portuguese held materially the same provinces: their legacy to Ceilao was the Catholic Faith. It is with Portugal that Europe makes an official or political rediscovery of Ceylon. But for ages she had been known in less intimate fashion. Marco Polo visited her. Mandeville had heard of her. Pliny is witness to a Sinhalese embassy to Claudius. Diodorus Siculus, Strabo and Ptolemy mention her. Ovid recalls ‘ubi Taprobonen Indica cingit aqua‘; and Milton: ‘the utmost Indian isle, Taprobane’.

Of all that ancient glory there now remain the ruins of Lanka’s cities scattered on the plain like some prodigious sermon on the doctrine of impermanence. There remains also that record of their reality, the great chronicle of Lanka, the Mahawamsa. The original work is a history of the kings of the Great Dynasty from Vijaya to Maha Sena, and was composed between the years 459 and 477 A. D. as a metrical exercise in the Pali language by the great historian, Mahanama. The second portion, relating to the Lesser Dynasty, was written in the same style in the reign of Parakrama Bahu the Great, about the year 1226, and later pens carried the story down to the end. The whole is now loosely called the Mahawamsa and makes one of the most extraordinary documents of the world. In all its essential qualities it is a characteristic Eastern work. In its style, a vivid sense of the picturesque and the figurative, at times exquisite, at others violently uncontrolled, blends with an equally arresting brevity and directness. Its wild flights of fancy and imagination are only balanced by its wilder desire for truth and actuality; and its occasional lofty idealism is only too often neighbour and near bred with its grim practicality. If it indulges in rhetoric, it can yet mirror an impressive spiritual sincerity and simplicity; if it labours in a chaos of confusions and contradictions, shifting muddledly between the affirmations of the Veda and the denials of the Buddha, it yet asserts a wider unity; if it shows crudity in parts, it is on the whole a good story.

Every chapter of the Mahawamsa finishes with the unfailing reminder that the work was written ‘for the serene joy and emotion of the pious’, or ‘equally for the delight and affliction of righteous men’. That is well, for its very breath and inspiration was the religion, or rather the system of conduct, which the Buddha raised on his celebrated ethic and metaphysic; and the test of such a record would be the application of Gautama’s precepts to the lives and achievements of the kings. To assert that kingship as portrayed in the Mahawamsa is an unmitigated despotism would be to judge it by a different order of ideas and a loftier philosophy of life, and by the experience of democracy which is the fruit of Christianity. If, in the Buddha’s synthesis, kings were born, kings had to make good that birth in the fulfilment of Karma, and by merit and mastery over self-deliver themselves, as their supreme teacher delivered himself and showed the way. The ideal king would therefore have been, however unfettered externally, at least hedged m by that fettering piety; but in practice there were not wanting those who took the gross evils of their society for granted and committed the extremes of violence and oppression. But on their memories the Mahawamsa has never failed to utter a terrible moral: that the abuse of greatness is when it disjoins remorse from power.

Yet there was no lack of prudent and benignant kings who kept the dharma, saved and strengthened the State, and brought it peace and prosperity In the history of some of these, as of the greatest of the Sinhalese rulers, Parakrama Bahu I, there is unfolded an ample proof of administrative methods which may be called constitutional and democratic; of the division and delegation of royal power through the channels of local and provincial government, of the regular observance of a public good and a public right, of popular consent and popular counsel. These indications are, however, casual and unimportant to the chronicler, who did not intend to be an Artistotelian critic of the constitution, but to extol wise and good monarchs. For, besides being an intensive glorification of the doctrines of the Buddha, the Mahawamsa is also a superb glorification of kingship, of the sovereign power and the sovereign duty, the whole business of the patriot king. It is a book of royal example. It is a King’s Book.

If it thus tirelessly presents the conclusion—‘therefore will the wise man continually take delight in works of merit,’—it is small wonder that it is a solemn and sustained panegyric of great kings. In its pages great kings are celebrated, magnified, and even raised into oracles and divinities. Of one of them, King Aggrabodi I, for instance, it is written that he was ‘surpassing the sun in glory, the full-orbed moon in gentleness, Mount Meru in firmness, the great ocean in depth, the earth in stability, the breeze in serenity, the teacher of the immortals in knowledge.’

But the writer does not quail before that colossal hyperbole; perhaps he need not, for hyperbole is not a falsehood but a figure, and a typically Eastern figure—symbolic of the richness of Eastern languages, of the tropical abundance of Eastern soils, and of the colour and life in the lands of the Sun. While the people showered on their kings barbaric pearl and gold, the poets showered encomiums on their royal lords and patrons. It is in this way that King Buddhadasa is set down as ‘a mine of virtue and an ocean of riches … .He entertained for mankind at large the compassion a parent feels for his children’. Kirti Siri Megha ‘was like unto a public ball of charity wherein all men were able to partake freely according to their necessities’. Vijava Bahu I was ‘a great poet and gave to many men who made songs wealth in great plenty with gifts of land … And the king who was much skilled in making songs in Sinhalese became the chief of tike bards of the Sinhalese.’ King Kasyappa V was a learned expounder of the law and skilled in all arts and gifted in discerning between right and wrong…. He watched over the people like his own eye’. Prince Jetthatissa ‘was a skillful carver…. Having executed several arduous undertakings in painting and carving, lie himself taught the art to many of his subjects. He sculptured a statue of the Buddha in a manner so exquisite that it might be inferred that he was inspired for the task.’ And the second Parakrama Bahu had read all the Buddhist scriptures, ‘purged them of faults’, and ‘translated them in due order from the Pali language into the Sinhalese tongue’.

Then there were the builders; and the chronicle revels in nothing so heartily as in describing those giant feats in stone, almost gloating over their size without, and lingering minutely over their beauty within. These were reared up from time to time and made the fame of the cities of Pollonaruwa, Anuradhapura, Mihintale, and later of Kandy; palaces, pyramidal dagobas, great temples and tanks and baths, some of which, on a conjecture from their scattered monoliths, may have added to the wonders of the world. But building always redounds to the fame of the builder: ‘The king had built sixty-four viharas and had lived just as many years.’

Action always serves to distinguish and immortalize the man of action. The brightest and most admirable writing in the Mahawamsa has been devoted and the pride and patriotism of the chronicler taxed to the utmost in the recital of the high epic of King Dutu Gcmunu (101-77 B. C.) and the splendid romance of King Parakrama Bahu the Great (1164-1197 A. D.). Gemunu is like any other of the figures of the old heroic age; but he not only looms like a giant, but led a knighthood of ten paladins of towering stature who were the mainstays of his army. With them he resisted the terror of his age, the Tamils from the South of India, who, having earlier invaded and forced a settlement in Lanka, carried fire and sword everywhere from their citadels. With an unwearied joy in the details of the chronicle follows Gemunu as he ‘fought victoriously through twenty-eight great battles.’ The climax of all was his Homeric joust with the Tamil king, Elara, in single combat, each riding on a stampeding and fighting elephant until Elara bit the dust. Whereupon Gemunu, with the heroic gesture of his age, ordered full royal honours to be given at the sepulture,’ and the hero’s tomb to be honoured for ever.

Twelve hundred years after Gemunu, the Great Parakrama was equally versed in war, and had even studied ‘the books that related to the business of war’. But, surpassing Gemunu, he achieved ‘dominion of the Island of Lanka without a rival’. Even as a youth he had nursed that dream; disguised and wandering about and joining in common games he learned the secret strength of his rivals. At the same time his study had been of the arts and sciences, religion, laws and language. He knew ‘the art of planning stories, dancing, music, reading, and the use of the bow’, and was ‘a leader of those who love music and poetry.’ To that proficiency in the humanities he added a stately character. His name meant ‘one whose arm defends others’; so h^ once asked : ‘If we render not help to him who seeketh refuge from us in his adversity, how then can the name of Parakrama Bahu be fitly given to us?’ And having trounced a royal adversary to abject surrender, he ‘yielded the subdued country to the vanquished king.’ ‘O, how marvellous was the fullness of his compassion!’ exclaims the chronicle. He remodelled the army, trained archers skilled in fighting by night, set up ramparts and fortified places, and after many hard battles all Lanka lay at his feet. Then he turned his thoughts to India in a long delayed war of revenge on his traditional foes, the Dravidians of the south. He built a fleet, manned it, said : ‘Bring hither to me a Sinhalese sword . . . . It is one that hath power in my hands to put an end to all the kings of India’-and all Pandya, of course, also lay at his feet. And having proclaimed the peace of Parakrama, he made laws; built wondrous temples and shrines; re-planned his cities with new and added delights; made a thousand tanks for irrigation, one of which men called ‘the Sea of Parakrama’; multiplied harvests, making Lanka ‘a perpetual granary’; caused wealth and plenty to flow to all; inspired poets to sing; brought in the Sinhalese Golden Age. ‘He was the greatest of far-seeing men’, says the chronicle. Again, in an ecstatic outburst.

‘Here is the power of merit, here is wisdom, here is faith in the Buddha, here is fame, here is glory, here is majesty exceeding great.’

And so there was. But the level of Parakrama was too high to keep long, and in mortal chronicles there are not always bright pages to write. Short reigns and violence broke the old order, and in the ensuing rivalries the united kingdom of Parakrama sundered again into bickering principalities. The rise of new feuds from within and, amid their cleavage, the return of old foes from without, were mild even as sensations and irrational enough as sense. Yet in their petty interlude occurred a third thing, too large to be noticed or chronicled in its largeness: the sails of Europe pointing eastward, and the dawn of a young and modern world. But the chronicle still goes on, retailing the palpably smaller things, most of them the absurdities of that disjointed time, some the rare traces of a former capacity. One of these rare traces is the fair episode of three brothers who, with benevolent rule, held the throne of Lanka. Here the chronicler recovers something of the rapture of his elders and the spirit of the old, unhappy, far-off things and battles long ago. He describes the three brothers; but in doing so he sums up kingship in Lanka.

‘Even as kings gifted with little wisdom, maddened by the beauty of Lanka, did that which was evil and came to great trouble; so they, who were endowed with wisdom and favoured by Lanka, did that which was right and acquired great fame. Even so, these three rulers of men who became the joint lords of a Lanka beautiful as she hath ever been, preserved peace and harmony among themselves. That, I say, is a marvellous thing.’