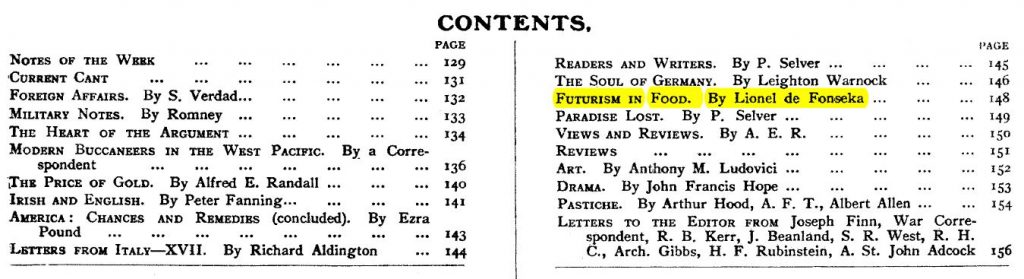

Futurism in Food

by Lionel de Fonseka.

The need for abstraction and for symbols is a characteristic sign of that intensity and rapidity with which life is lived to-day.

Our modern complexity prevents us from being satisfied with a pictural and anecdotal expression. . . The time has gone by when the painter painted as the bird sings. . . . Art is now, before everything else, perception and expression.

There is, to my mind, but one artistic tradition among the painters of the West—that of Italy. It is to the Italian tradition that the most advanced painters of our day are attached.

A picture should be a world in itself. . . So long as education and habit allow the public to look at a picture without thought of exterior realities, it will make no further endeavour to see what the picture possesses in common with those realities; it will not trouble itself as to what the picture represents, but it will be influenced by the purely pictural charm of its form and colour. . .

We asserted in our technical manifesto that ” We shall no longer give a fixed moment in universal dynamism, but the dynamic movement itself.” Our idea has not met with comprehension. . . .

In the realm of Art everything . . . is a matter of synthesis.

If musical rhythms or a metaphysical or literary idea, are evolved from our pictural expression, so much the better, for this establishes the complexity of our Art. . .

I believe that every sensation may be rendered in the plastic manner. . . .

The Impressionists, in painting the atmosphere surrounding a body, have set the problem; we are working out the solution. . . .

Since the forms which we perceive in space, and which our sensibility apprehends, undergo incessant change and renewal, how are we to determine beforehand the manner in which these forms should be plastically expressed? (From the manifesto of Gino Severini, Futurist Painter.)

The Post-Impressionist Restaurant had proved a failure, at least so far as I was concerned. Rathbone, who in his leisure hours inhabits a studio in Glebe Place, had invited me to dine there with him one day last summer. The Petit Gascon, as the restaurant was called, was just coming into vogue with that section of London aesthetes which fills the gallery at Covenv Garden night after night during the Russian Ballet season.

“Of course,” said Rathbone, “it is a truism nowadays to say that Nature imitates Art. It were curious none the less to observe the influence of Art in the ver. exercise of our natural functions—in our eating and drinking for instance. I daresay you will find everything rather strange just at first at the Petit Gascon, but in time as life keeps pace with art, you will find that even the ‘good, plain cooking’ of our lodging-houses will take the principles of Post-Impressionism into account.”

I was frankly interested in our experiment of the Petit Gascon. As we entered the restaurant I saw s red-faced baby lying on the middle of the floor, floating Moses-like in a basket on a linoleum sea. “This,” said Rathbone, as he stooped and tickled the baby’s chin, “is the proprietor’s son—a little Gascon. He is a symbol. Of course,” he went on, “we try to make our symbols as simple and as comprehensible as possible. Our movement, in a way, is a revolt from the intricate and far-fetched symbolism of some previous schools.”

The decoration of the restaurant roused my curiosity. The walls had been painted by some of the younger artists of the Post-Impressionist school. One painting represented the Garden of Eden and our first parents in purple, but without linen. There was an apple tree in full bloom, and I noticed some detached apples which, instead of falling to the ground, flew upwards into the air. I was puzzled by the phenomenon and questioned Rathbone. “Rhythm of a sweeping and salient character,” he told me, “is one of the first principles of our school—and in this instance the apples are rendered saliently. We endeavour as far as possible to regard the world with the naive, direct vision of primitive man. The apples dart upwards in this painting because the artist had retrojected himself into a time before the Law of Gravitation had been discovered. You will note also, by the way, the salient sweep of Eve’s glance. In fact, that glance is used invariably in Post-Impressionist productions whenever the human eye is represented. That is really the explanation of the recrudescence of the Glad Eye in real life recently.”

These details of our surroundings, however, were but incidental matters which I regarded with comparative indifference. The dinner itself was sufficiently arresting. I found that the chef had, indeed, carried out the principles of the Post-Impressionist School with rigorous logic. He had calculated the digestive powers of primitive man to a nicety, and the sauces were prepared on the basis of a shrewd guess at the predilections of the primitive palate, innocent of the culinary sophistications of centuries. I admitted to Rathbone that the dinner was a rational conclusion from Post-Impressionist premises, but as food it was a failure, as both my palate and my digestion refused to make the rather strenuous imaginative effort required of them.

It is not to be wondered at then that I was sceptical and unenthusiastic when Rathbone proposed the other day that we should dine at the newly-opened Futurist restaurant. But Rathbone was persistent and assured me that this was altogether a new departure on entirely different principles from those of the Post-Impressionists. “The basis of the new system,” he said, “is perseprion and expression. Hitherto we have been at the mercy of our food. That was all very well in the primaeval simplicity of human intelligence and consciousness. What do the uninitiated do even now? They go into a restaurant perhaps and order any dish which attracts their palate without reference either to the properties of the food or their own emotional state at the time. They take no account of the subtle correspondences between certain dishes and certain states of our consciousness, of what there is in common between dishes and inward realities. As things are a dish induces a mood; but rightly considered, a dish should not induce but express a mood. We believe that every emotion may be rendered gastronomically— and there are immense possibilities in food as a medium of expression. What is Art, after all, but conscious expression? The new grace before meals will be an examination of consciousness—a few minutes’ introspection before dinner and you become aware of your dominant mood and order your food accordingly. The objective table d’hote dinner is a thing of the past. Of course the public cannot be expected just at first to choose the correct dishes in the new subjective manner, so at the Moderno you inform the chef of your emotion of the moment, and he sends up the corresponding dish.”

I consented eventually to try the Moderno a few days ago. The evening was wet and dreary, and I longed to be in some sunnier clime. I informed the waiter that my dominant feeling was one of “nostalgic des pays inconnus.” He brought me some mock turtle soup. Rathbone told the waiter he felt insignificant and was given some whitebait. The cause of Rathbone’s feeling of insignificance, it appeared, was some misunderstanding between himself and his wife. I thought it strange as I had always found his wife sympathetic. I next confessed to a feeling of “amitie amoureuse” and was given a vol-au-vent Heloise. Curiously enough Rathbone and I shared the next feeling—cynicism. I expected caviare; Rathbone thought we should get Welsh rarebit. Instead the chef sent us creme caramel. ‘rSurely,” I said, “there has been some mistake.” Perhaps the waiter had misunderstood us; but no, he had duly reported our feeling of cynicism. The manager then intervened. “The chef is always pleased,” he told us, “to explain his methods to the public in puzzling cases of this sort. Of course he is the artist, and you, as the public, must submit to his ruling and accept his symbols without question, but if you care to see him, he will doubtless explain to your satisfaction that creme caramel does really express cynicism. And, by the way, before you go down, let me draw your attention to Rule 15 of the establishment:—” In all interviews and communications the chef must be addressed as Signor Antonio.”

We went down and interviewed the chef, who proved to be a red-haired Irishman. “Signor Antonio,” I said, “I fear there has been a mistake somewhere. We confessed to cynicism, and you have sent us creme caramel, but surely there is no correspondence between them.”

” Ah,” said Signor Antonio, “I fear you have not studied our technical manifesto very carefully. Consider this: We shall no longer give a fixed moment in universal dynamism, but the dynamic movement itself. Now, I grant you that caviare would in the ordinary way express cynicism. But by the time you are conscious enough of your cynicism to confess the feeling, you are no longer cynical, but fighting against your sentimentality, and I express sentimentality by creme caramel. The slight flavouring of pepper indicates your subconscious protest against the feeling of sentimentality. I hope I have made it clear.”

“I am at a loss, Signor Antonio,” I answered, “as to what I should say. If I admitted that it was quite clear, that would dismiss the complexity of your Art, and you, Signor Antonio, would become, with painful plainness, simple Tony.”